The Week's Economic Reports

Saturday, January 20, 2007

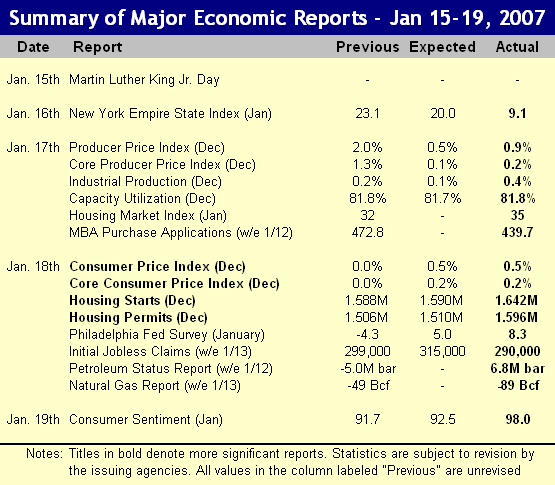

Following is a summary of last week's economic reports. Consumer sentiment at three-year highs highlighted a week of mostly positive reports - the uptick in both producer and consumer prices is likely to prove temporary given the recent slide in energy prices. For the week, the S&P 500 Index was unchanged at 1,431 and the yield of the 10-year U.S. Treasury note was unchanged at 4.77 percent. NY Empire State Index: The Empire State index fell from the mid-20s level of the last three months to just 9.1 in December indicating a manufacturing slowdown in the New York region (at least for the month). This was the lowest reading since the months of April and May in 2005 and, prior to that time, you'd have to go back to 2003 to see a reading this low. Declines were paced by new orders and inventories while prices increased slightly.

NY Empire State Index: The Empire State index fell from the mid-20s level of the last three months to just 9.1 in December indicating a manufacturing slowdown in the New York region (at least for the month). This was the lowest reading since the months of April and May in 2005 and, prior to that time, you'd have to go back to 2003 to see a reading this low. Declines were paced by new orders and inventories while prices increased slightly.

Producer Prices: Producer prices for finished goods increased more than expected in December, the overall index rising 0.9 percent after a 2.0 percent gain in November. Core producer prices, excluding food and energy, rose only 0.2 percent after jumping 1.3 percent the prior month. For the year 2006, overall producer prices were up 1.2 percent and the core rate rose 2.0 percent.

As would be expected from looking at the most recent monthly change, most of the latest increase occurred in food and energy. The energy price index rose 2.5 percent led by heating oil (up 4.0 percent) and gasoline (up 0.7 percent) - both of these increases are expected to be reversed in the next report. The food price index rose 1.7 percent led by a sharp increase in the price of fresh fruit and vegetables (up 21.7 percent), costs that are sure to go higher as a result of crop loss in California over the last week.

Industrial Production/Capacity Utilization: Industrial production exceeded expectations in December, rising 0.4 percent, while capacity utilization stayed level at 81.8 percent. Production gains were paced by durable goods including automobiles and computers, motor vehicle output rising 2.6 percent in December after a 3.4 percent gain in November.

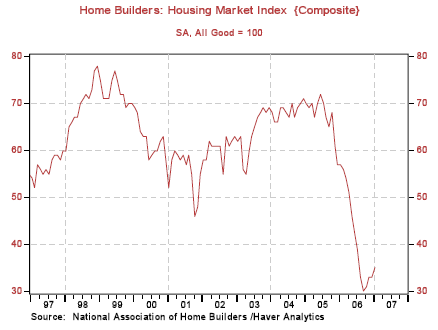

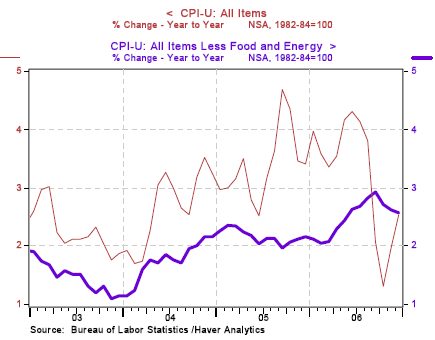

Housing Market Index: The home builders' housing market index posted its third gain in the last four months after bottoming in September at 30. The September mark was a 15-year low after eight consecutive months of decline. Much of the uptick must be due to bouncing off of such a low level as home builders continue to face major problems with inventory, pricing, and land option write offs. Present sales have improved, largely a result of huge incentives and price reductions, while warm weather contributed to an increase in traffic of prospective buyers. Consumer Prices: Overall consumer prices rose 0.5 percent in December and the core rate of inflation was 0.2 percent - this follows no change to either measure of inflation during the month of November. For the entire year of 2006, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 2.6 percent after increasing by 3.4 percent in 2005. Core inflation was also 2.6 percent in 2006 versus 2.2 percent in 2005.

Consumer Prices: Overall consumer prices rose 0.5 percent in December and the core rate of inflation was 0.2 percent - this follows no change to either measure of inflation during the month of November. For the entire year of 2006, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 2.6 percent after increasing by 3.4 percent in 2005. Core inflation was also 2.6 percent in 2006 versus 2.2 percent in 2005.

Rising energy prices boosted the overall price index in December, the energy index increasing 4.6 percent led by gasoline and natural gas prices that rose 8.0 percent and 3.9 percent, respectively. Much of this will be reversed in next month's report since most energy prices have fallen dramatically since the December reporting period ended. For the year 2006, energy prices rose 2.9 percent versus an increase of 17.1 percent in 2005.

In December, price increases were seen for transportation and apparel, up 1.8 percent and 0.6 percent, respectively. Within the housing component (comprising 40 percent of the overall index), rental prices increased 0.5 percent and owners' equivalent rent rose 0.3 percent. Offsetting these increases, prices for new cars fell 0.2 percent along with airline tickets that were down a full 1.0 percent. It really is hard for people to understand the inflation figures provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics - what has happened in the U.K. over the past few months is likely a preview of coming attractions here in the U.S. After a growing number of individuals voiced their concern that the government's inflation numbers do not represent their real-world experience, The Telegraph took up their cause and, soon after, a personal inflation calculator was added to the government's website. Using this calculator, individuals can enter their own consumption data and a "personal inflation rate" is calculated.

It really is hard for people to understand the inflation figures provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics - what has happened in the U.K. over the past few months is likely a preview of coming attractions here in the U.S. After a growing number of individuals voiced their concern that the government's inflation numbers do not represent their real-world experience, The Telegraph took up their cause and, soon after, a personal inflation calculator was added to the government's website. Using this calculator, individuals can enter their own consumption data and a "personal inflation rate" is calculated.

An initial report from The Telegraph shows "personal" inflation rates as multiples of the government's overall inflation rate, with seniors hit particularly hard. As expected, government economists scoffed at the results.

A personal experience is worth sharing here as well. The same turkey on wheat sandwich (no cheese) that I've been buying for many, many years now has gone from $2.70 to $3.40 in just the last few years. That is an increase of more than 25 percent or two to three times the reported rate of inflation during that time. Lunch entrees are now around $6, up from below $5 a few years ago, and it is amusing to see the look on the faces of visitors who spend almost $10 for an entree, a soda, and a cookie - in a cafeteria.

If it weren't so difficult for people to assess how prices are rising all around them there would be many more complaints, however, if events in the U.K. are any indication, look for "inflation unrest" here in the U.S. before long.

Housing Starts: Warm weather contributed to a healthy 4.5 percent rebound in housing starts for the month of December. The total of 1.642 million units rose substantially from the downwardly revised level of 1.572 million in November, however, gains were restricted to multi-family construction as the number of single family homes built continued to fall. For the year 2006, total housing starts were down 24.7 percent.

The number of permits issued for new home construction rose 5.5 percent in December, following almost a year of monthly declines. For the year 2006, permits were down 24.3 percent. Those cheering the headline for this report as confirmation that housing has bottomed will surely be disappointed as unseasonably warm weather skewed the data and single family home construction continued to decline. With the onset of an arctic chill in much of the country, a reversal may be in store next month.

Philadelphia Fed Survey: After wallowing in negative territory since September, the Philadelphia Fed's survey of regional manufacturing activity surprised to the upside in January registering 8.3 following a December reading of -4.3. New orders gained and shipments increased sharply while most other categories were about flat.

Consumer Sentiment: The outlook from consumers has improved dramatically since bottoming last summer in the low 80s. Excluding months affected by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, last summer's readings on consumer sentiment were the lowest since early 2003, the recent rise no doubt a result of lower energy costs. The current level of 98 is a three-year high and was driven largely by a hefty rise in the expectations component, the public now seeming to believe that the high energy prices of last year were an aberration.

Summary: A misleading housing starts headline, mixed regional manufacturing reports, and an increase in prices that will be reversed next month were all eclipsed in significance by a remarkable rise in consumer sentiment last week. Following on the heels of the prior week's surprisingly strong retail sales report, it seems that the consumer is in sharp disagreement with those who continue to be bearish on the economy in general and housing in particular.

Most people don't pay close attention to business news and as a result, comforting headlines like last week's report on housing starts have clearly contributed to an improved outlook. With the exception of shortages in certain fields, there is no stress in the job market and when considering that most homeowners have no idea if and how the value of their home is changing, as long as energy prices remain low this optimism is likely to persist for some time supporting the consumption that drives the U.S. economy.

The Week Ahead

Economic news in the week ahead will be highlighted by more data on the housing market - existing home sales on Thursday and new home sales on Friday. Other reports include the Conference Board's leading economic indicators on Monday and durable goods orders on Friday.

[Note: This is one small part of the Weekend Update published at the companion investment website Iacono Research. Since it contains no investment-specific information, it will appear here on Saturdays on a fairly regular basis. To have a look at the complete Weekend Update, including the model portfolio and much more, sign up for a no-obligation free trial today.]

All charts courtesy of Northern Trust.

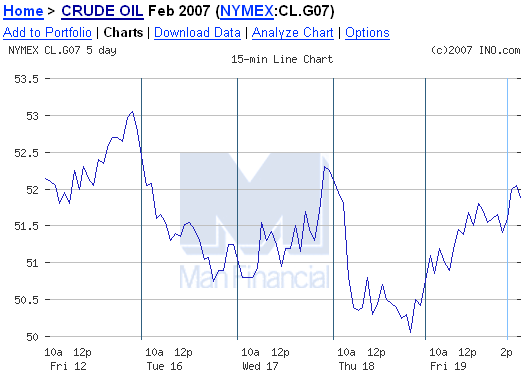

The oil companies did well. They can still make pretty good money with $52 oil - the new Congress, however, that's a completely different challenge.

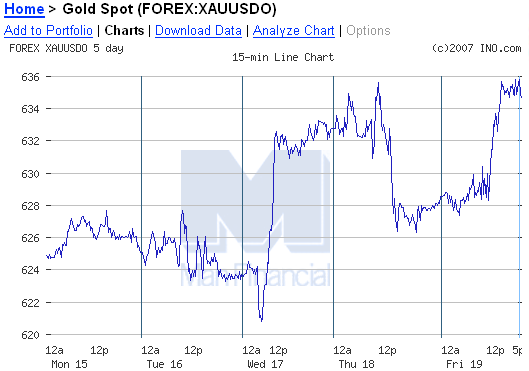

The oil companies did well. They can still make pretty good money with $52 oil - the new Congress, however, that's a completely different challenge. What happened on Wednesday?

What happened on Wednesday? The gold miners continue to struggle.

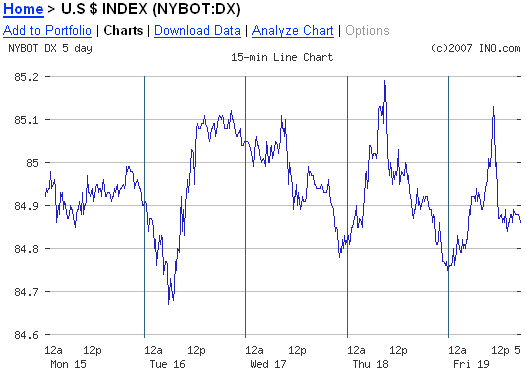

The gold miners continue to struggle. And the dollar looks like an EKG this week.

And the dollar looks like an EKG this week. So far this year it's been one brutal sell off and two weeks of steady gains - 49 weeks to go.

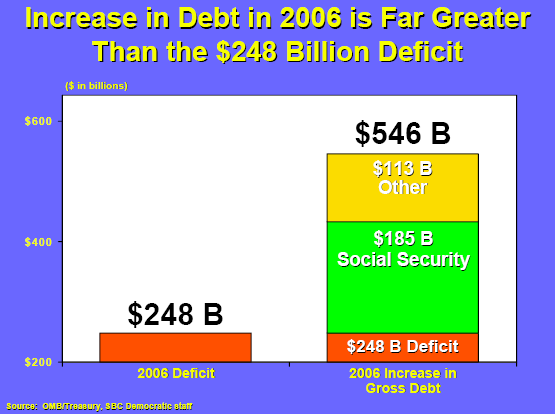

So far this year it's been one brutal sell off and two weeks of steady gains - 49 weeks to go. Congressional hearings have a whole different feel now that the Democrats hold the gavels. For the last ten years the first 20 minutes of a session such as this would have been consumed by eight or ten elected officials heaping praise on Alan Greenspan for the fine work he was doing.

Congressional hearings have a whole different feel now that the Democrats hold the gavels. For the last ten years the first 20 minutes of a session such as this would have been consumed by eight or ten elected officials heaping praise on Alan Greenspan for the fine work he was doing. Although increases in house price have recently moderated in some countries, they still are very high relative to rents. Furthermore, with the exception of Germany and Japan, the ratios of house prices to disposable income in many countries are greater than what would have been predicted on the basis of their trends.

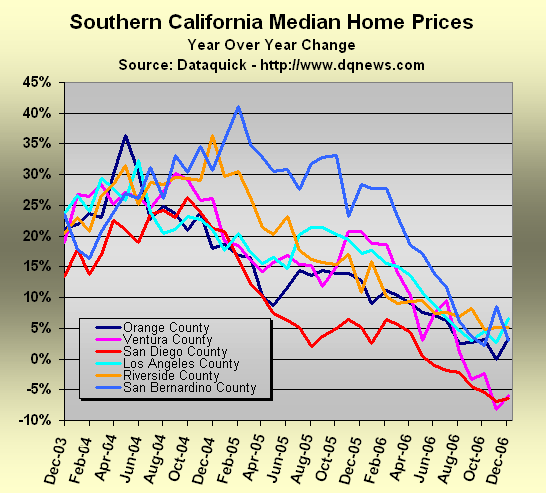

Although increases in house price have recently moderated in some countries, they still are very high relative to rents. Furthermore, with the exception of Germany and Japan, the ratios of house prices to disposable income in many countries are greater than what would have been predicted on the basis of their trends.  If the end of civilization as we know it

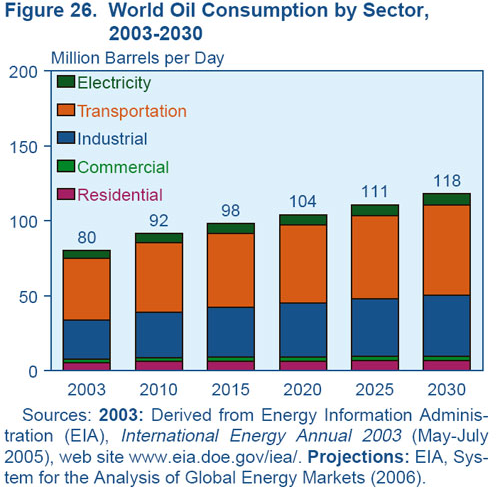

If the end of civilization as we know it  The second chart is from the

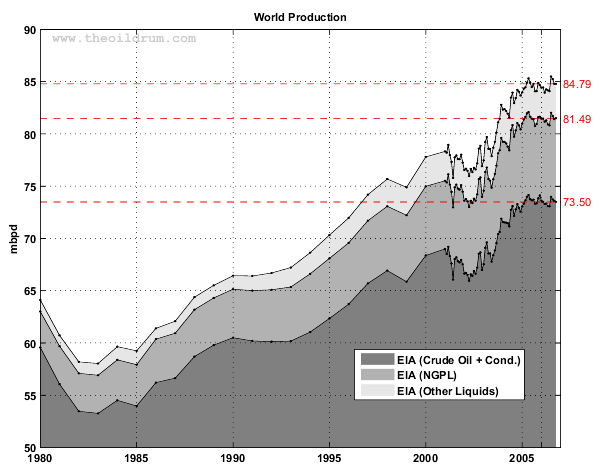

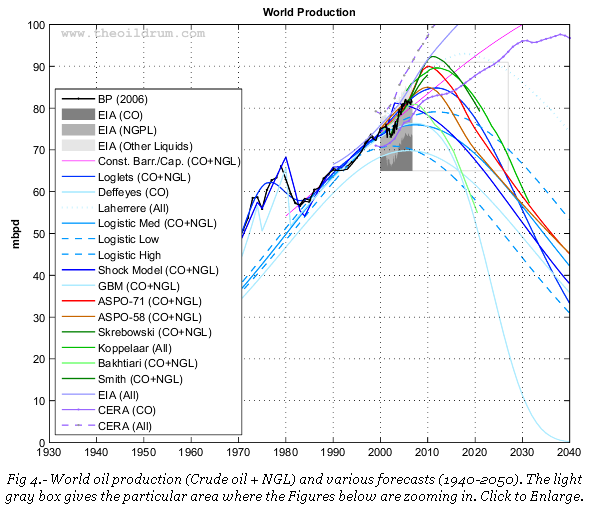

The second chart is from the  Chart number three below (also from Khebab at TOD) is where things get complicated.

Chart number three below (also from Khebab at TOD) is where things get complicated. Which line will prove to be the correct one? Who knows.

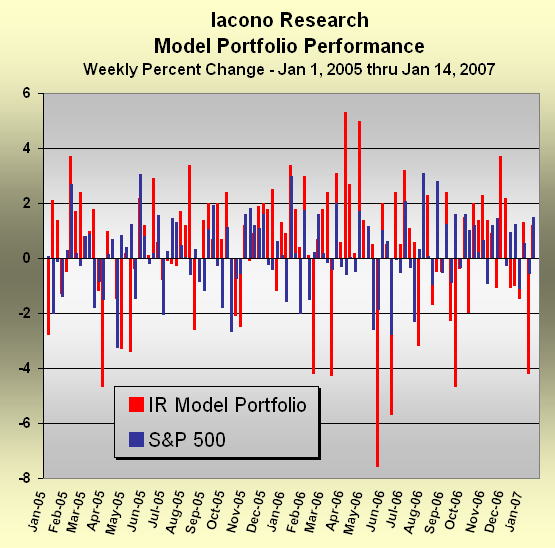

Which line will prove to be the correct one? Who knows. Also note the increased volatility - this takes a little while to get used to, but it's worth it.

Also note the increased volatility - this takes a little while to get used to, but it's worth it.

When she adds up her monthly bills for her mortgage, car loan, electricity, gas, water and phone, they exceed her income from Social Security and a part-time job by almost $200.

When she adds up her monthly bills for her mortgage, car loan, electricity, gas, water and phone, they exceed her income from Social Security and a part-time job by almost $200. Some attribute oil's fall to the mild winter in the northern hemisphere, which saw New Yorkers sunbathe in early January. But copper has also been plunging in price, which cannot be blamed on the weather. Other metals have been dragged down in copper's wake. The Economist All-items commodities index, which excludes oil, fell 10.2% in the week to January 9th (see chart).

Some attribute oil's fall to the mild winter in the northern hemisphere, which saw New Yorkers sunbathe in early January. But copper has also been plunging in price, which cannot be blamed on the weather. Other metals have been dragged down in copper's wake. The Economist All-items commodities index, which excludes oil, fell 10.2% in the week to January 9th (see chart).

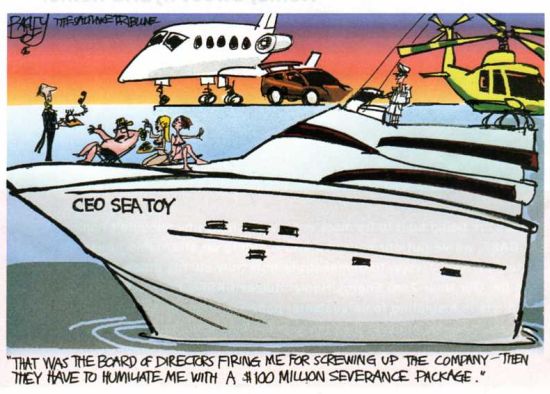

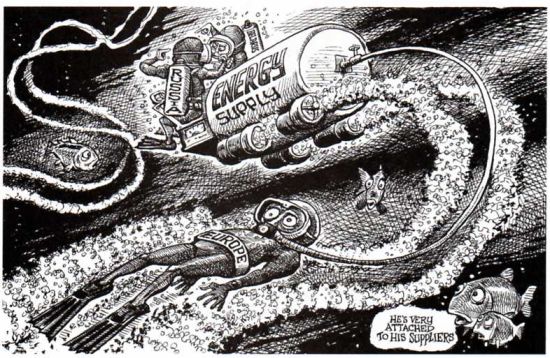

The cartoon artists at The Economist work with fewer colors but sharper wits.

The cartoon artists at The Economist work with fewer colors but sharper wits. They've done a great job with tables in the back of The Economist as well, now combining economic data for emerging markets along with developed nations.

They've done a great job with tables in the back of The Economist as well, now combining economic data for emerging markets along with developed nations. It must be terribly tedious and boring to collect and publish this data week after week - all those asterisks and funny cross-like symbols. It's doubtful that if mistakes are made anyone notices. They could just be making up these numbers.

It must be terribly tedious and boring to collect and publish this data week after week - all those asterisks and funny cross-like symbols. It's doubtful that if mistakes are made anyone notices. They could just be making up these numbers.