Turning Out As We Expected

Monday, June 13, 2005

Before further exploring last Thursday's appearance by Alan Greenspan before the Joint Economic Committee, let's briefly revisit Friday's post, specifically, the answer to Rep. Ron Paul's question about debt. Let's put a chart next to the response that was provided when Rep. Paul asked whether we, in this country, are fooling ourselves about our prosperity by creating so much debt.

Here's the response:

Greenspan: Well, I think we learned very early on in economic history that debt, in modest quantities, does enhance the rate of growth of the economy and does create higher standards of living, but in excess, creates very serious problems.Here's the chart:

To the untrained eye, this would appear to be an amount of debt that is more "excessive" than "moderate", especially when laid next to income, which rises gently. The scariest part is that the curve keeps getting steeper - was this the real "revolution" that Reagan started?

Rep. Saxton Throws Softballs

Taking another look at the question and answer session, in particular the second question from Committee Chairman Rep. Jim Saxton of New Jersey, we learn some interesting things about the use of the word "inflation" and also about expectations the Fed had regarding their policy decisions in 2001. Here's the transcript, which starts 28 minutes into the CSPAN video (see the Video/Audio section).

Saxton: In this morning's Wall Street Journal, there is an article which credits past Fed policy for cushioning the effects of the collapse of the stock market and the tech spending bubble in 2000. At the same time, the article suggests that accommodative Fed policy has instead contributed to a housing bubble.Before we get to the good part, it is interesting to note the use of the word "inflation" here. Apparently, this word can be used to describe the 2000 stock market, as in the "severe inflation of a bubble", but official "inflation" statistics, in the form of the CPI or PCE, can not include stock prices. Similarly with housing, we can have "inflating" home prices, but this variety of inflation can not be a part of official inflation statistics (in this case rental equivalents are included instead).

It seems to me that given the enormous shocks to the economy from the collapse of the stock and technology bubble in 2000 that the Fed did the right thing in relaxing monetary policy, in retrospect, perhaps could have done that even sooner. The thrust of Fed policy seems to have averted what could have been a much more serious economic fallout from the popping of the bubble in 2000.

Looking back, do you believe that, the Fed relaxation of monetary policy after the bursting of the bubble in 2000 was the best course given the risky conditions at the time?

Greenspan: I do, Mr. Chairman. We couldn't draw that conclusion at the point we were implementing the policy because we knew that in the process of what we were doing, that was addressing the consequence of a very severe inflation of a bubble, carried with it potential side effects. As best we can judge, things have turned out reasonably as we had expected, both positively and negatively.

But in our judgment, the positive effects of the policy far exceeded the negative ones, and we decided at that time it was the appropriate policy to initiate and while it's too soon to judge the final conclusion to how all of this turns out, I think that given the same facts and the same conditions we would have made the same ... implemented the same policy.

Since the conclusion in the prepared remarks refers to "underlying inflation that remains contained", and inflation was similarly contained in 1999 and 2000, it seems obvious that the only kind of "inflation" that is allowed to be counted as part of "official inflation" is "benign inflation".

Things Have Turned Out Reasonably As We Expected

So, since lowering interest rates to historically low levels in 2001 and holding them there for two and a half years, "things have turned out reasonably as we had expected"?

This is what mortgage borrowing has looked like the last two decades:

As everyone watched the share price of Cicso and Amazon rise in the late nineties, there was enough confidence to increase mortgage borrowing slightly, but look at 2001 thru 2004! And, 2005 is expected to be another record year - and they expected this to happen?

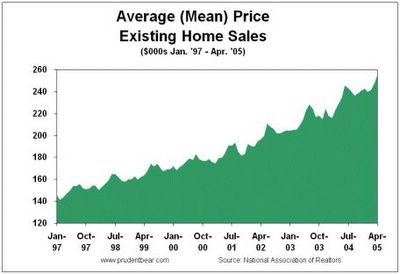

This is what home prices have done in the last ten years:

Low interest rates and easy lending terms caused people to borrow more and pay more for homes, thus bidding up home prices. Everyone likes rising home prices - it makes you feel wealthier and spend more.

You would think that with dramatically rising home prices, home equity would now be at an all time high - sure, some of the home equity would be spent, and the economy would be stimulated, but generally we'd all own a higher percentage of our homes. Right?

This is how much of our homes we own, as a percent of home values:

So even with dramatically rising prices, people own less of their homes? How could that be?

Apparently, even with housing prices which have risen dramatically in recent years, people are spending their home equity faster than home values are rising - and they expected this to happen?

But, then it's probably alright that all this money was spent on goods and services - after all, the economy needed to be stimulated. But which economy is being stimulated and in what way?

This is a look at our trade deficit for the last 15 years:

So, people are spending their home equity faster then home values are rising, but we have an increasingly large trade deficit. While we create housing related jobs in this country to build and sell more homes, and while we create service jobs in this country to enable selling of more goods to homeowners flush with home equity, the goods that these homeowners seem to be buying come increasingly from overseas.

From overseas where manufacturing jobs are being created in record numbers - and they expected this to happen?

Boy, the weekend bender analogy seems to be more and more applicable - why worry about a hangover, when there's more booze? The immediate positive effect of more alcohol outweighed the negative effect of dealing with the overconsumption of alcohol and the unavoidable hangover.

Maybe we should have just stopped drinking in 2001.

Charts courtesy of the Grandfather Economic Report and Prudent Bear.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

2 comments:

I like the story, but the first chart should be on a logarithmic base. all linear longterm charts show a dramatically steepening curve which I consider the graphic equivalent to polemics.

Does that chart include communal debts as well? The latest debt stats from the Fed show a decline in net borrowing by the Treasury but the debt of the states explodes which I attribute to the reduction of social spending on the federal level.

These costs now seem to have been transferred to the non-federal level.

If this were a single data series I would agree, but it is the divergence of the two data series that is significant here, not just the rising debt.

I have no idea about communal debts - I'm just starting to dig into the Fed data.

Post a Comment