The Yield Curve

Monday, December 19, 2005

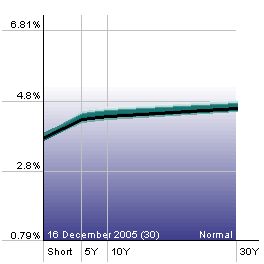

The flattening of the yield curve has been much talked about lately and there will be plenty more talk in the coming months. For those new to this topic, the yield curve is most often represented by a chart with U.S. Treasury yields of varying durations - shortest on the left, longest on the right - at a particular point in time.

Readers are again directed to the always informative Dynamic Yield Curve over at StockCharts.com, where many hours can be spent investigating some of life's economic and financial mysteries. To the left is the yield curve as of March of 2003, around the time that U.S. equity markets hit their lows for the decade. Economic growth, as measured by real GDP, had gone negative for a few quarters in 2001 and 2002, and heading into 2003 was uncomfortably in the two percent range.

To the left is the yield curve as of March of 2003, around the time that U.S. equity markets hit their lows for the decade. Economic growth, as measured by real GDP, had gone negative for a few quarters in 2001 and 2002, and heading into 2003 was uncomfortably in the two percent range.

To make matters worse, job creation was anemic and people were talking about the dreaded "deflation" monster.

Still reeling from the stock market bubble and the 9/11 tragedy, growth, job creation, and inflation were much too low for the folks at the Federal Reserve.

While long term rates have held generally above 4 percent in the last few years, the 10-year note occasionally dipping into the 3 percent range, the difference between short term rates and long term rates has been at least two or three percent during this time.

This is a highly stimulative condition, as with no apparent limit to the amount of money available to be borrowed, many have seized the opportunity to borrow at low short-term rates, seek a higher return elsewhere, and pocket the difference. This is otherwise known as the "carry trade".

This has worked well in the U.S. until short term rates began rising last year - today it only works well in Japan, where short-term interest rates have been near zero for the better part of the last fifteen years, following the zenith-like rise of their economy in the 1980s.

To the right is what the yield curve looks like today. The difference between long-term rates and short-term rates has narrowed precipitously since June of last year as short term interest rates have moved from 1 percent to 4.25 percent in a series of 13 quarter point hikes. During this time rates for the 10-year Treasury actually fell from 4.6 percent to 4.4 percent.

Thus the conundrum.

Why have long-term rates refused to move up as short-term rates have risen?

Why is this a conundrum? Why is this significant?

Because a continuation of the current trend will cause an inverted yield curve.

What's Wrong with an Inverted Yield Curve?

An inverted yield curve has been the single most reliable economic indicator in predicting coming weakness in the economy - it has, in fact predicted the last five recessions. In an article from yesterday's L.A. Times, Tom Petruno explains:Normally, long-term interest rates are higher than short-term rates, which makes sense. If you're going to tie up your money for a lengthy period you would expect to be compensated for the risks that entails.

Hmmm...

When short-term rates exceed long-term rates, an "inversion" is said to occur. The last one was in 2000: The Fed held its key rate at 6.5% in the second half of that year. But as the economy weakened, bond investors began to sense that the Fed soon would be easing credit. Long-term bond yields slid.

By the end of December 2000, the 10-year Treasury note yield was 5.11% — about 1.4 percentage points below the Fed's short-term rate.

The Fed began cutting its rate in January 2001, but it was too late. A recession began in March.

That has been par for the course, according to David Rosenberg, an economist at Merrill Lynch & Co. in New York. In the last three decades there have been five Fed-induced rate inversions, Rosenberg said.

"The economy slipped into recession a year later all five times," he said.

"Too late" in cutting rates and "Fed-induced" rate inversions leading to recessions - that's not something that you hear a lot about. The Fed is supposed to be assuring things like price stability, maximum sustainable growth, and full employment, not "inducing" recessions by cutting rates too late.

In fact isn't "inducing" a recession really the domain of 1980s Fed Chairman Paul Volcker? Does anyone think of current Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan as inducing recessions? There have been so few recessions in the last 18 years, and comparatively mild ones at that.

But, back to the yield curve...

Given the course that has been taken for the last year and a half, and should current trends continue, an inverted yield curve would likely appear sometime in the first few months of 2006, as short-term rates move up to between 4.5 and 5 percent. It's been almost four years since the ten-year note was over five percent, and it shows little inclination of late of cooperating anytime soon. It seems the only way to avoid a rate inversion would be to stop raising short-term rates.

But, maybe this time it's different. Maybe an inverted yield curve in this new era of global trade and international finance is not such a big deal. The L.A. Times article continues:This time around, however, no less than Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan himself has said that an interest-rate inversion might not signal an economic slowdown. The implication is that the bond market has its own special issues these days.

"So much money is looking for a place to go" - now on the surface it sounds like there could be a lot worse problems than having too much money. And, there is no question that U.S. debt is popular with our overseas trading partners, who coincidentally, on a monthly basis, have just about exactly the same amount of new savings as the U.S. has new debt. That is very convenient for a nation such as the U.S. that would much rather spend than save.

...

Some on Wall Street believe that demand for bonds has remained robust, keeping yields down, because of a global savings glut — meaning that so much money is looking for a place to go that investors in effect are forced to out-compete one another for bonds, depressing returns.Some analysts also contend that bond yields have softened because the market believes inflation has been vanquished in the long run, the jump in energy prices notwithstanding. Government bond returns have averaged 2.3 percentage points above the inflation rate since 1926. If inflation falls back to, say, 2%, a 4.44% bond yield would look fairly generous.

So much money but so little inflation - inflation has been "vanquished in the long run" - a savings glut and low long term interest rates to keep mortgage rates low to enable the continuation of the world wide real estate boom.

Again, it's hard to see where the problems are here. What is everyone concerned about with this inverted yield curve?

It appears that we are living in the most perfect of all possible worlds. The only thing that doesn't make sense is why gold is rising so dramatically.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

19 comments:

Is this any way to run an economy? Is this sustainable?

I dunno. Ask your friendly neighborhood banker.

I think hedge funds and big banks making money via the carry trade is supposed to stimulate the economy - not necessarily in a good way for the little people, but stimulate the economy nonetheless.

the gold thing concerns me also. 1 unlikely theory goes like this.

a bunch of traders are shorting the long bond in anticipation of inflation.

As we all know, shorting temporarily raises prices. (bond prices up, yields go down).

--

gold could also be completely seperate story. a nation like russia may be anonymously accumulating lots right now. Same goes for any oil producing country.

Remember, in the past a large portion of the US long term debt was domestically held. Today, much of that debt is held by foreigners who may believe that it pays to continuing to reinvest in the USA despite rising short term rates. This could lead to a flattening of the yield curve as oly a small portion of US debt holders move to gold. The portion moving to gold can explain the rise in this price.

econmaster: There is a multi-layer story to what you mention.

1)It is natural that "domestically" held debt is down, due to tax consequences and lack of anonyminity for an american. It is much more convenient for the debt to be owned outside the US. For this reason it is very unclear who is really buying these bonds.

2)Regardless of who is buying these long bonds. They would only be doing so with expectations of profit. China and Japan think long-term. They aren't simply buying bonds just to have american's buy cars and electronics "now". There is some type of long term plan with these long bonds.

"Regardless of who is buying these long bonds. They would only be doing so with expectations of profit"

yes and no. The do not expect a direct profit on their bond purchases. They expect the indirect profit of stimulating the US economy and thus their exports. China figures (wrongly) it'll come out ahead in the end by over purchasing US Treasuries.

But then they'll wise up and stop, or slow down as they lose too much on the T-bills and not enough of a gain on the exports.

Then pow.

http://housingpanic.blogspot.com

Tim,

I think your question is rhetoric. Or, perhaps you want to see if readers come to the same conclusion ... or have read Mises.org.

An inverted yield curve is just the result of the Fed taking away stimulus. It may signal but does not cause a recession. Taking the stimulus away from an economy that is already 'goosed' naturally causes it to slow. If stimulus is not removed, the recession or worse is still unescapable.

Gold is rising because markets are telling you that the Fed is trapped. Without further stimulus, the economy as we have it will collapse. It needs to in order to liquidate malinvestments. Yet, the further and greater stimulus that is needed to forestall the reckoning does so only temporarily and at the price of a more devastating end.

chubbyray,

I have many more questions than conclusions (particularly when it comes to the timing).

My question "What is everyone concerned about?" is indeed rhetorical - there are lots more important things to be concerned about today than whether an inverted yield curve can still predict recessions.

And, I've been wondering all day about the gold comment - it just kind of came out.

Tim,

I think the issue of timing is like trying to predict when the volcano will blow or when the earthquake will happen, how it will happen. All we can be sure of is that the accumulation of stress (i.e. real debt) has reached very dangerous levels and the trend shows only signs of accelerating. It will be released somehow. It can't just go away. The smart money is increasingly nervous and is buying insurance (PMs). And ... of course, you can't buy earthquake insurance during the earthquake.

Why does there have to be inflation for gold to rise? Maybe countries are invest ing more in gold because it is beginning to look like a safer investment than the US Dollar.

Inflation = devaluation/debasement of currency = money printing

Rising USD prices = falling USD buying power are the result.

Only when it becomes wholly evident that USD value is falling, paper currency holders will be motivated to exchange for hard currencies like gold and silver.

chubbyray: under your simple logic inflation = devaluation = money printing = lower long bonds.

but thats not holding true.

i'm more under the assumption of a flight to quality. hence, higher gold prices and lower long bonds.

well we finally hit an Inversion between the 2 year and 5 year notes. Looks like bets are being made on the recession.

Dan,

The dynamic that is different now compared to, say, the 70's is the industrialization of Asia. This is holding long bonds up ... for now.

Totally agree, world trade is taking a much bigger role.

But to say that Asian banks are simply buying all these long-bonds with anticipation of inflation / loss of value over the long term does not make sense.

Imagine if we have deflation in the US. Quite a few of these long-bond holders will be able to buy up incredible amounts of assets at discounted prices.

The japanese / chinese / american's buying long bonds don't care about the "GDP". These are individuals that want to gobble up more assets, regardless of a recession.

symbolic question: When did Hearst build hearst castle?

Dan,

I think the answer is that large central banks don't have investment as a goal. When you can print, err steal, what you need who cares about investment gains? For China in particular, recycling USD into USD bonds is a strategic move that helps them build infrastructure and transition the workforce into modern economy. They simply cannot avoid concluding that the debt will be defaulted on in one form or another. But, there are ways to mitigate its full impact. And ultimately, it is a small price to pay for modernizing the country. Besides, 30M people (I think it's 30M) entering the modern workforce per year have to find something to do. If they don't, there is going to be big bad trouble.

I don't see that private investors anywhere really believe USD long bonds are an investment. However, they may rent them for a while. I don't see USD deflation happening at all. When the debt defaults do start, we will have deflation in hard currencies; of which, gold and silver are the two best.

chubbyray,

Why do you rule out deflation?

Dan,

Just to be sure we're talking about the same thing. I'd rule about USD deflation = decrease in USD supply -> lower USD prices because:

(i) There is simply too much debt accumulated. USD deflation would crush the indebted.

(ii) We live in a social democracy where constituents can vote themselves benefits. Nobody is going to vote in a truly responsible government.

(iii) There is no escape and the path of least resistance will be debasing the currency. It's what central banking has always done and it's what the Fed has been doing for nearly a century now.

Try Faber's last few articles for a great explanation.

The ultimate conclusion to a bust is always deflation. When the debts are defaulted, the real money supply measured in hard currency will shrink and general prices relative to hard currency will go down (i.e. $5000/oz gold is deflation in gold terms but inflation in USD terms)

Japan, China, et. al., buy US bonds to devalue their currency which reduces long term interest rates in the US...the Fed can not stop this...

Post a Comment