Neoclassical Economics, Neuroscience, and Asset Bubbles

Monday, January 23, 2006

Reading economics blogs can provide real insights into how contemporary economists view the world. Understanding how economists think can go a long way in explaining why they say the things they say and how decisions affecting millions of people come to be.

Reading economics blogs can be fun too, as some economists maintain a quirky, yet lovable, sense of humor. This may sound like an odd view for a blog with a name such as this one, but not really.

Long ago, we made the invaluable observation that most people go through life looking for confirmation of what they already believe. Only a small minority constantly seek new thoughts and opinions or, better yet, views that are contrary to their own.

Only a select few desire a constantly expanding base of personal knowledge and a sort of testing, as it were, of privately held views to repeatedly evaluate whether these views merit continued belief.

That is what this blog has in common with Dr. James Hamilton's blog - there may not be much else.

Dr. Hamilton is a Professor of Economics at the University of California, San Diego and writes the blog Econbrowser. It has been nominated for awards and is very popular. Today's post was inspired by an item that appeared last week on Dr. Hamilton's blog titled, The Neoclassical Paradigm.

It began with the circumspection, "Do economists have a sensible way of thinking about the world?"

Dr. Hamilton goes on to describe neoclassical economics, brain imaging studies demonstrating how financial decisions can be driven by emotion, and offers the following reasons why neoclassical economics is still valuable:

He concludes by offering hope that Homo economicus, though flawed, offers the only enduring model of the actors that drive an economy.

Neoclassical Economics Today

So, what is neoclassical economics? It is composed of three principles:

This all seems to make good sense when the preferences involve laundry detergent or Popsicles, or when decisions are made in fairly well controlled environments, but does this model really apply to asset classes such as equities and real estate?

With the recent history of a stock market bubble followed by a housing bubble, is this model still useful? Specifically, as to the three tenets of neoclassical economics,

Until ten years ago when asset prices began their meteoric rise, aided by new technology and the participation of individuals as never before in history, none of these questions seemed germane to mainstream economic thought.

Stocks were purchased by wealthy individuals or pension funds, rather than common laborers - the intricacies of trading on Wall Street were unknown to, and out of reach of, the common man.

The barrier to entry for housing was much higher than it is today - both interest rates and lending terms were far less accommodative and real estate was considered a place to live and raise a family, rather than as an investment or a source of income.

Given the restricted set of actors up until about ten years ago, claims of rational behavior, utility maximization, and good information seemed reasonable to make.

But, with today's "ownership society", ordinary people are required to make more and more decisions that will affect their economic well-being in very tangible ways. And, with a delayed feedback mechanism inherent to stocks and housing, this model seems less applicable.

Today, decisions seem to be much less rational and information used to arrive at these decisions, while plentiful, seems to be increasingly suspect. At the same time, the desire to maximize happiness seems to be stronger than ever.

The Mortech Example

Consider the case of a typical subprime borrower visiting the office of the Mortech Financial Group, as discussed in these pages last week. Is the decision to buy property a rational one, when, by any historical measure, this property is wildly overpriced?

After completing the purchase using a very non-traditional type of financing, this market participant becomes a price-setter, adding a data point for all those who look to make similar purchases in the future.

Though this purchaser's decision was based more on monthly payments than price paid, the price paid affects other market participants in very profound ways.

Whether the buyer really understood the terms of the agreement to which he is now bound, or its long-term implications, the price paid becomes the measure against which other home values are judged.

The Lessons of Neuroscience

As in the case of the subprime borrower, emotions play an important role in decision making today - recommendations from friends and family, falling in love with the kitchen, and male adequacy in providing for a family all factor into the decision making process.

How emotion affects decision making has been the subject of increased study in recent years as discussed in Dr. Hamilton's post last week, where he looked at the Ultimate Game experiment as detailed by Princeton psychology professor Jonathan Cohen in these recently published works:

The neural basis of economic decision making in the ultimatum game (PDF)

The vulcanization of the human brain (PDF)

The Ultimatum Game works as follows:In this game, a pair of partners is given an endowment that they must split. One partner proposes how to split the sum, and then the other may accept or reject the offer. If the offer is accepted, each player is allotted the proposed amount. If the split is rejected, neither partner receives anything, and the game is over.

So, even in the case where there is no time element involved, the rational calculation of the partner choosing whether to accept or reject the split becomes emotion-filled and irrational - a present reward is forfeited with no offsetting future benefit, so that the other partner can be punished for the slight.

Standard economic theory suggests that any split offering a small but nonzero amount should be accepted. After all, for the partner who must decide whether to accept or to reject the offer, something is better than nothing. However, offers of less than about 20 percent of the sum are routinely rejected, even though this means getting nothing. Any non-zero offer, it seems would be beneficial to the partner making the accept/reject decision, yet when an offer of below 20 percent is tendered, often times strong activity is triggered in parts of the brain associated with "negative emotional responses such as physical pain and disgust".

Any non-zero offer, it seems would be beneficial to the partner making the accept/reject decision, yet when an offer of below 20 percent is tendered, often times strong activity is triggered in parts of the brain associated with "negative emotional responses such as physical pain and disgust".

This normally leads to rejecting the offer.

In a similar experiment reported in this Wall Street Journal article last July, a study concluded that people with a certain type of brain damage made better investment decisions than others. The participants had damage in an area of the brain that controlled emotions which prevented them from feeling fear or anxiety, and as a result, in the simulated investment game, they came out ahead of their unimpaired competitors.

When studying the brain activity as it related to decision making in a game of speculation and expectations of future monetary reward, they concluded the following. In one study, the pair used gambling games and neuroimaging techniques to look at what part of the brain is triggered when people anticipate winning money. They found that monetary rewards trigger the same brain activity as good tastes, pleasant music or addictive drugs.

Yes, the anticipation of monetary rewards stimulates the same area of the brain as good food and addictive drugs, rather than areas associated with higher cognitive functions.

Still Useful?

So, in today's world of an increasing number of decisions to be made by more people, amid a rapidly increasing amount of sometimes conflicting information, during an era of multiple asset bubbles that can quickly reward and belatedly punish risk takers, is neoclassical economics still useful?

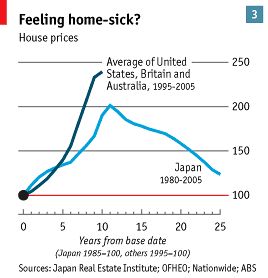

In response to Dr. Hamilton's rationale above, it hardly seems that the reward or punishment intended to mitigate the influence of emotions comes in a timely enough manner to affect future investment decisions. The nature of asset bubbles is that they go on for long periods of time - everybody comes to believe that it's different this time, and then reality sets in.

Deferred punishment for irrational exuberance in the late 1990s was not meted out until years later. Time will tell how the housing bubble resolves itself, but surely punishment awaits many.

As for unsuccessful, emotional investors removing themselves from the markets, it seems the opposite is true, and to a large degree. Emotional investors, momentum traders, and condo-flippers become emboldened and then draw other emotional investors into the market - the essence of a speculative mania.

In the end, an early exit would have saved many late adopters from much anguish. Those cajoled to join the real estate investment party in 2005 will likely have been better served if the condo-flippers were removed in 2004.

And lastly, does neoclassical economics provides a structured and disciplined approach to modeling behavior such as that seen in today's asset markets?

Who knows?

Things might be a lot easier to understand without all the bubbles.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

12 comments:

The first axiom must be modified to "rational within their own model of the world". Anything else imputes something on actors which is not be there. That will go a long way of explaining what you call "irrationality". Hey, what can be more rational than satisfying your own urges, as opposed to freaking out from constant denial of gratification?

I believe the undocumented immigrant customers of Mortech are a poor example for this post. A U.S. citizen with sub-prime credentials, especially one in today's post-"reform" bankruptcy law environment, is a better example.

Why? If those illegals have been cashing out their equity appreciation these last few years via home equity loans, and investing the proceeds in the mother country, they have an easy out if the market goes the wrong way and their payments go ballistic. They can just leave, go back home, bribe an official to change their name and transfer their assets to the new name, and live happily ever after. How is anybody EVER going to find them to repossess anything other than their home? They don't exist.

The illegal immigrant/subprime borrower is gone!

Wow, that may be the first of many times we hear that expression in the years to come.

I concur that this was a poor example as they may be the most rational of all subprime borrowers.

I don't think there is any conscious plan connecting equity extraction and expropriation but both are certainly going on. IIRC something like 15% of the Mexican economy is US transfers. As to them "leaving." No, they'll disappear and a few months later show up with a new mustache saying, "oh, you are looking for my cousin." Just one more Greenspan induced problem; porous borders and liqufied asset values.

The DDM does quite well in explaining the hyperbolic tendencies of prices when the risk adjusted return approaches the growth rate. Even when everyone realizes it can't last, it can last for longer than most people have patience, and even when it is over, people will try to breakeven. Some will attempt to time the market while others will convince themselves to buy and hold even though the time may not be right.

Here is an alternative rational explanation of the observed behavior in the Ultimatum Game, which requires neither a) the expectation of repeated plays in the future nor b) an irrational impetus to punish perceived unfairness. Namely, an outcome for Tom which is much larger than the outcome for Bob may be perceived by Bob as a real threat to his own well-being: Tom will be able to outbid him for purchases, or buy up more of a limited resource, etc. The threat is neatly obviated by Bob's rejection of the offer. Tom probably understands this aspect of Bob's position (rationally or otherwise), and his "irrational" offers approaching fifty percent do not seem unsound.

So perhaps the real balancing for Bob's decision occurs not along a moral continuum of fairness vs. unfairness, but between the danger of having nothing on his own (starvation, say) and the danger of having too little in comparison with Tom.

The real question for neuroeconomics, it seems to me, is the old one of correlation vs. causation. Does some negative-emotional activity in Bob's brain cause him to act, or is it merely correlated with his act, which may somehow turn out to be rational after all? Perhaps the realization that he can't trust Tom does indeed disgust him; perhaps the feeling of disgust teaches him to avoid Tom. Nevertheless, perhaps the emotion which really "causes" his decision is fear/safety, based on a very real evaluation of the economics of the situation, rational or otherwise.

I worry that the fledging subject of neuroscience may be engaged with a fallacy: "Now that we can actually see the real workings of the brain, we can finally get down to the real causes of human behavior." But who is going to interpret those mysterious blips on the brain scanners? After all, the blips themselves do not cause anything; they are merely observations. At best, they can be correlated with other events, such as emotions reported simultaneously by the scannees. But if we ask Bob why he rejected Tom's offer, and he says "because the size of it made me angry", are we really so much better off now that we can stare at the scanner and reply, "yes, I can see that"? More precisely, to what extent could we have made the same economic/psychological arguments without the scanners?

I read some of the study and they said that in one of the experiments they did, the reactions were different based on whether the human player thought he was playing against a computer or another human. When playing against another human, the imaging showed much greater emotion. Maybe that's why slot machines are so popular.

I think your own blog contains the answer to the riddle you've posed.

On the one hand, the average mortgage holder *has* behaved rationally, because he has been behaving based on the information (read: advice) given to him by nearly everyone.

On the other hand, how can this be the standard practice, if this information is so clearly wrong?

But you've already solved the mystery. Its because our national policy is one of propagating the wrong information.

Everything the Fed has done in the past ten years has been giving a not-too-subtle nod of approval to irresponsible practices in the marketplace (specifically, real estate). The fed, when it decided to take reasonable action (raising interest rates, demonizing "creative mortgages"), quickly put a stop to the bulk of the unwise practices.

Now if only they'd stop taking on debt themselves like there's no tomorrow.

You seem to think things are getting worse in terms of grassroots capitalism--that the regular person's ability to make wise decisions in the marketplace is declining. In fact, I think they are getting much better, if only because of the internet.

Some proof: I just finished reading Ric Edelman's tome, and he had a nice example of the term life insurance market. Abruptly, in the late 90s, term life insurance prices plummeted. Why? Because now you could get comparative quotes on the internet, and there were free, easy-to-use, independent online brokerage services. Consumers got more perfect information, and rents vanished.

And I probably need not say much about the joys of the typical internet "marketplace" tools (ebay, edmunds, pricewatch, ad nauseum...)

It seems to me that if the government would just quit intervening irresponsibly, this process could proceed more monotonically in the positive direction. Until this happens, I don't see how you can determine whether the change in consumer behavior is self-driven or driven by engineered national macroeconomic policy.

I enjoyed the post and have three comments:

1)

When evaluated through the lens of utility maximization, I'm not sure there's anything irrational about the gamer rejecting the low but non-zero split offer. The key to making the transaction rational is correctly valuing the utility provided by "getting even" with the other player.

To prove the theory, you'd need to run the game with actual amounts that are in some proportions of the players overall wealth. For instance, if the rejecting player had a net worth of $1 million dollars and the amount rejected was $100, the decision could seem entirely rational.

2)

IMHO, the idea that the irrationality of asset prices is the result an influx of inexperienced market participants misses the mark. Professionally managed mutual funds (especially tech funds) didn't fare any better in the stock market crash than individuals. Also, the market for commercial property (often owned by pension funds and other "experts") has enjoyed a run-up similar to residential property in the current bubble.

Temporary bouts of market imbalance are equal-opportunity and they do a great job of humbling experts and novices alike.

3)

Despite my criticisms, I do believe that neoclassical economics has much to offer in helping us parse out the seemingly irrational behavior of markets and market participants.

I think where the tools fall short is in helping us to quantify the information gaps that plaque market participants. Too much of the information required to make sound market decisions is unknowable and participants find themselves in a guessing game. In these cases, where the signal to noise ratio is too low to provide meaningful guidance, market participants cede control to the emotional twins of fear and greed.

A very nice post. I would highly recommend the book Descartes Error that discusses the role emotions play in so-called rational thought:

href="http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/014303622X/qid=1138117710/sr=2-1/ref=pd_bbs_b_2_1/002-3528210-6724804?s=books&v=glance&n=283155

What if you are rational but just plain wrong? What if you are right for all the wrong reasons?

Post a Comment