Three Sins, One Gift - Sin #3

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

[This is part three of a four-part series which concludes next week as Alan Greenspan steps down after eighteen years as chairman of the Federal Reserve. Parts one and two, Ignoring Asset Prices and Bending to the Will of Others, have appeared in recent weeks]

Sin #3 - Fostering a Culture of Debt

Over the last two decades, departing Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan has affected many people in many ways. Few people understand the impact he has had on their lives - how he has helped transform a culture. After eighteen years as the world's most powerful central banker, he has changed the way people think about money, credit, and most importantly, he has changed the way people view debt.

After eighteen years as the world's most powerful central banker, he has changed the way people think about money, credit, and most importantly, he has changed the way people view debt.

Debt, a pariah to generations following the Great Depression, has been embraced by recent generations.

Recent generations, that is, who are now far enough removed from the tragedy of the 1930s that history's lessons of excess credit and debt have been forgotten. Debt, always a tempting seductress, has been raised to new levels of respectability under the tutelage of Mr. Greenspan.

Many, emboldened by rising asset prices, have completely lost what had been for centuries a largely uninterrupted natural aversion to borrowing money.

Benjamin Franklin and Adam Smith abhorred debt.

Changing Attitudes

Today, borrowing against equity in real estate occurs at rates never seen before. Mortgage equity withdrawal was unheard of generations ago - a second mortgage was the last recourse for a family in trouble.

Today it is routine.

Septuagenarians shake their heads as they see young people living lifestyles which don't square with what they know of their incomes and expenses. Debt it seems has not taught any hard lessons lately - debt has become too friendly, too tame, and too forgiving.

Nowhere is the cultural change more apparent than on television - a constant din of pitchmen offering new and innovative ways of extending credit to ordinary people.

"I'm up to my eyeballs in debt" one ad begins, as if that condition is somehow funny.

In a truly disturbing symbol of how times have changed, the once mighty General Motors now hawks home equity loans and EZ cash-out refinancing through its Ditech.com subsidiary - the only GM group that has been consistently profitable in recent years.

A once dynamic and innovative economy has become increasingly dependent on borrowing money to fund consumer spending. This spending, in turn, produces economic growth and most accept this condition as just another reality - another fact of life.

With a zero savings rate, Americans borrow and spend paying little heed to the mounting debt or the implications for the future. As long as asset prices rise faster than debt, household balance sheets don't seem to matter, and bills never really come due.

Someday, maybe soon, the accumulating debt will matter.

Household Balance Sheets

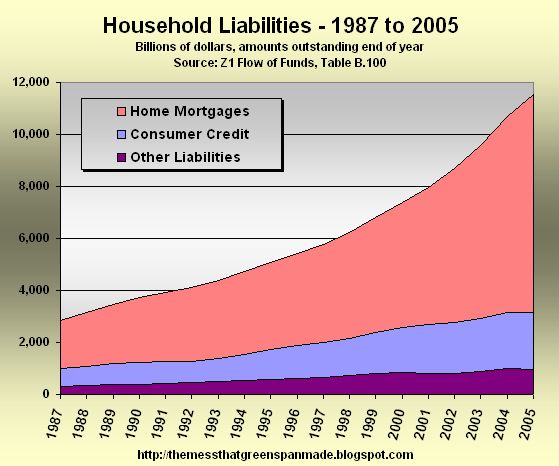

The magnitude of the new debt over the last two decades is evident when looking at household liabilities over this period. Household debt gently rose during the 1990s until the bursting of the stock market bubble necessitated massive monetary stimulus from the Fed.

The stimulus came in the form of multi-generational lows in interest rates which, when combined with a largely unregulated mortgage lending industry, ignited a housing boom the likes of which the world has never seen.

That's a lot of mortgage debt - over eight trillion dollars in all. In the last three years alone, nearly three trillion dollars of new mortgage credit has been extended - first mortgages, second mortgages, home equity loans, and lines of credit.

Some dismiss concerns of too much debt by pointing to the bottom line.

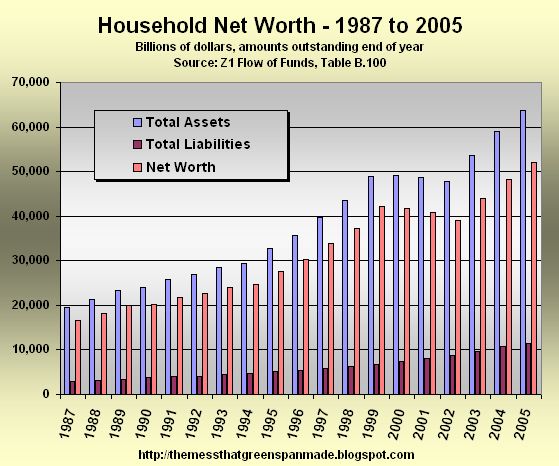

Debt, they say, is not a problem because household balance sheets are the best they've ever been. Today, household net worth does look impressive - against a meager 12 trillion dollars in debt stands a hefty 64 trillion dollars in assets.

A closer look at net worth, however, shows that while liabilities have marched steadily upward, assets can go up or down. Not down by much, at least not in this chart, but down nonetheless.

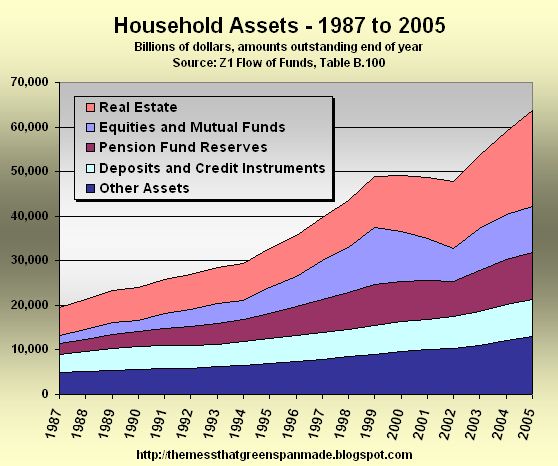

A closer look at how different types of assets have behaved during the first half of the decade shows a neat handoff between equities and real estate. Stocks had run their course, interest rates were slashed to forty-year lows, and housing markets across the land began to boom.

One rapidly rising asset class having exhausted itself, another asset class began to rise rapidly, easing the pain that, historically, would have been expected.

A crisis had been averted. In fact, many would say that the cure worked better than could possibly have been expected, given the circumstances.

In the last few years, with soaring property values, household net worth has now hit all time highs despite the trillions of dollars in new mortgage debt. More debt, it seems had not only saved the day, but ushered in a new era of prosperity and rising living standards.

Ordinary people are now wealthier than ever before, and the effects of more credit and debt have confirmed what many had come to conclude over the years - debt is good.

The cultural transformation is now complete.

A Good Time

But as Alan Greenspan prepares to exit the stage, leaving behind mountains of debt, where does that leave us? With all this new debt and prosperity comes a potential problem.

What happens if real estate assets suffer the same fate as equities did a few years ago? Or, what if real estate values simply go flat for an extended period of time?

Since debt lingers long after assets lose their glow, how might the bottom line look then? How might the culture change as a result? Warren Buffet famously said some time ago, "Give me a trillion dollars and I'll show you a good time too!".

Was this Alan Greenspan's motive all along?

With almost nine trillion dollars of new household debt created during his years at the Federal Reserve, and having changed the way the entire Anglo-Saxon world views debt, is this all that Alan Greenspan ever really wanted?

To show everyone a good time?

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

6 comments:

This is a great posting.

What happens if real estate assets suffer the same fate as equities did a few years ago? Or, what if real estate values simply go flat for an extended period of time?

I would say that this is not the relevant question. The relevant question is, "What happens if incomes go flat, such that they are no longer able to service the debt?"

As long as incomes are able to service the debt, nothing of significance is going to happen to real estate prices.

But, if the incomes of middle Americans are no longer able to service the debt, then we might get some foreclosures, dropping real estate and asset prices, and a cultural and political change.

So, it might be worthwhile to think abvout incomes, asking questions such as, "What will 60-70,000 layoffs in the auto industry do to the ability of the middle class to service its debt, not just in Michigan, but nationwide?"

Another thing, and maybe this is a subject for another post: it seems to me that it is way, way too easy to get consumer credit these days. It seems like everything, from cars to china, gets sold on the "no interest" loan program. Are retailers able sell anything without having to extend seller financing these days?

ok, you really need to lighten up for the rest of this week with what's coming up next week!

good reading, nice charts

tim, your greenspan farewell pieces are great ,and i broadly agree with your fears on real estate. however these can take a long time to unravel .the late 80's bust in the uk was precipitated by base rates rising from 9% in 88 to 14% in 89 .the bust in japan likewise saw a sharp rise in rates as the BOJ struggled with service price inflation .

it's the SPIKES that hurt ,and obviously the FED are trying to finesse. THe real estate market in the uk has looked dangerously overbought on affordability etc etc since 2000 ,but it continues because the economy is steady ,rates move gently ,and the real estate market rotates regionally.

i don't disageee at all with your bearish focus ,but quite what is going to be the conjunction of negatives that forces a bear market on us and when is tough.a number of people are upbeat on business capex finally kicking in....that could delay the end a while yet.

The 1920s and this decade show so many similarities. Then people were buying stocks on ridiculously low margins, nowadays they buy houses on even less margin.

Now the US faces the dilemma either to prop up the value of the $ by the way of higher interest rates which will prick the housing bubble or to continue going easy which will bring higher import prices, pricking the consumer bubble.

Taking it from history the Fed will first remain on the easy side too long and then turnaround 180 degrees and tighten too much. What chaos the focus on a single monetary policy instrument can create...

Would be interesting to undig the figures for prices of a house, car, suit, dinner etc. when paid in gold now and then.

Yesterday there was a spot on Orlando radio station- Centex homes is giving up to $50,000 off if you buy a home this saturday. You also get a $5000 gift card at Best Buy (for the giant Plasma TV?) if you buy any house. May be the beginnings of cracks in the market.

This morning an article in Florida Today spoke about a slowing in the real estate market in Brevard County. Ofcourse real estate agents say it will be a soft landing with appreciation of a "normal 5-6%, and at worst a 25% decline". How's that for soft?

Paid in Gold...

Well I don't know about the 20's but...

I recently read in an editorial piece in the local newspaper that

the writer had entered the work force in 1966 at the rate of $1.98/hr. He also stated that workers at the local steel mill were earning $3.00/hr. at the time.

This means that the average Joe in America was earning appox. $100/week(2.50 x 40).

or

Since Gold was $35/oz in 1966...

approx. 3 ozs of Gold.

Which means that if "Joe" still had

the same job, paying the same 3 ozs of Gold per week, without ever getting a raise, his job would currently be worth the equivalent of $85,000 FRNs per year!!!!!

(3 x 550 x 52)

Since we know that the median income today is around $45,000 we

now fully understand the "2 income trap" phenomena.

But wait, I forgot the punchline...

Average Joe 1966 was only paying 20% of his pay in State, Local & Fed Taxes while today's rate is north of 30%.

Thank You Mr. Greenspan, Woodrow Wilson, Paul Warburg(Daddy Warbucks), Colonel House, et. al.

Post a Comment