Occasional Paper No. 1

Monday, March 06, 2006

Late in the day on Friday of last week, the Treasury Department released a new report titled Petrodollars and Global Imbalances. It contains all sorts of great information about the enormous amount of oil and U.S. dollars that are sloshing around the world, but the most intriguing aspect of this report, at first glance, is that they chose this as the first subject for a series of "occasional" papers.

While the casualness of this characterization belies the significance of the subject matter, the "addicted to oil" theme does seem to be spreading in the nation's capitol.

It's hard to believe that in 1998 oil was selling for near $10 per barrel. This was largely a result of the Asian financial crisis, an event that continues to influence behavior today. The difficulties experienced during that time and the manner in which they were resolved have resulted in a broad-based risk-averse approach to international trade and global finance in much of the rest of the world.

While at the same time, these events cemented the role of the U.S. as the proverbial father who bails his son out of jail for youthful indescretions. Recall that Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, and Deputy Treasury Secretary Larry Summers were dubbed the "Committee to Save the World" by Time Magazine for their efforts at that time, in conjunction with the International Monetary Fund.

Few in the West appreciated the severity of this crisis, as we were all in the midst of an internet and technology boom, while illicit White House encounters were heating up. There was a brief lull in the stock market euphoria that had gripped the country, but the Asian Financial Crisis was largely a non-event across the Pacific.

These events go a long way in explaining the nature of global imbalances we find today.

In seven years, $10 oil turns into $70 oil. The aging father figure turns into a bit of a free-loader, constantly needing to borrow money while living a lifestyle he really can't afford - money which the maturing son is all too happy to lend because their relationship since the crisis has resulted in great prosperity and stability.

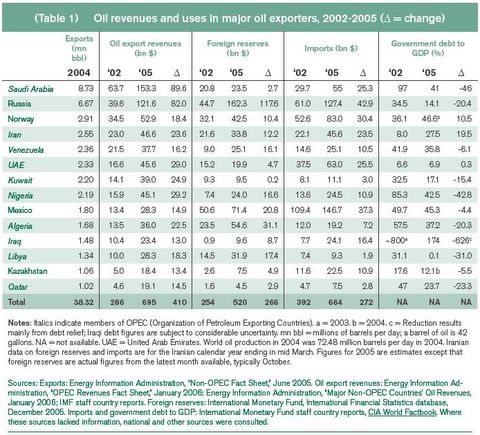

Meanwhile, petrodollars pile up in oil exporting countries at an unprecedented rate in order to perpetuate this relationship, and life goes on. Take a look at this table from the Treasury Department report to see where oil and dollars have been flowing.

Click to enlarge

The first item of interest in the chart above is that oil export revenues have more than doubled in the three-year period from 2002 to 2005. Saudi Arabia and Russia alone have accounted for nearly half of this increase, with Russia more than tripling its oil exports during this time.

What are they doing with all these petrodollars?

By and large, they are doing responsible things - building up reserves and paying down debt. Their imports have increased, but only by a fraction of the increase seen in their oil exports. Recall that a few months ago, Vladimir Putin made clear Russia's intention to exchange some of the paper money held as reserves for more tangible money in the form of gold.

During this time, China has emerged as the second leading importer of oil, behind the U.S., where much of the increased demand is a result of their booming export business with the U.S. This trade relationship is evident in the changes to current account balances for the same time period as shown below.

Click to enlarge

So, the U.S. goes from a dangerous level ($475 billion) to a critical level ($759) with no reversal in sight, while China racks up a huge positive change to their annual current account without the benefit of the relatively easy job of pumping oil out of the ground.

Note the standing of Germany in the chart above - a large swing in exports relative to the rest of Europe and all other non-oil exporting countries, and notably, one of the very few Western countries not experiencing a housing boom. Is there a connection there?

The more you think about it, the more unbalanced it seems to be - the U.S. borrows money from Asia to buy their exports, while the Middle East and Russia supply both the U.S. and Asia with oil at ever-rising prices.

Think of the oil exporters as being "the house" in Las Vegas - the U.S. and Asia are in a high-stakes game of poker, where the U.S. keeps losing hand after hand, but the Asian poker players continue to lend money back to the U.S., so the game can go on.

They are both having a swell time.

Meanwhile, "the house" continues to take their cut on every hand and as the dealer tires, the house cut increases. Both the U.S. and Asia would like for the game to continue indefinitely, but it is looking more and more like "the house" will determine when the game ends - either by making it prohibitively expensive for the players to continue or by exhausting the supply of cards.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

7 comments:

Update for the second table: The Eurozone already runs a current acccount deficit, latest figure minus 21 million Euros; data ECB.

Actually, the "House" in your hypothetical poker game is the Bank of Japan, which has recently advertised to the whole casino that it, perhaps as early as the day after tomorrow, it will stop giving out chips for free.

This has caused a whole lot of high-rollers to take their "easy money" bets off the table. As this process continues, the whole gambling industry is likely to see a reduction in business.

I response to your comment about Germany having a C/A surplus and no housing bubble:

It is also worth noting that the eurozone yield curve is not inverted.

Kinda makes ya go "hmmm."

Another way to lower our dependence on foreign oil is to pull the troops out of Iraq, stop pestering the Iranians or whoever else wants to sell oil in euros, or whatever, let Chavez pipe as much as he wants to China, and forever quash develop in the Arctic wilderness reserve. The price will go up accordingly and everyone will seek out the alternatives.

Yes, and also ask the Chinese and Japanese to please use most or all of their USD reserves to create national strategic petroleum reserves.

I agree with Matt Simmons when he says that low energy prices are a curse. One of the consequences of much higher energy prices would be a revival in local manufacturing labor markets. There is no point competing with Asia on wages. But, if it costs a lot more to transport, that will support local manufacturing, local agriculture, local everything. $100 oil, $200 oil, it cannot come soon enough to save our economy.

Hey PJP stop spamming blogsphere!

Post a Comment