The Economist Does Commodities

Monday, July 24, 2006

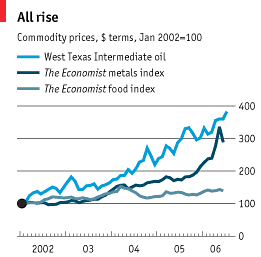

In the current issue of The Economist, once again, more value is found in sections other than the one for which the magazine is named. In the Finance and Economics section this week, another anonymous economist comments ($) on the oddity of rising commodity prices in an age of low inflation.WHEN commodity prices slipped from their giddy highs in May, many observers hailed the beginning of an inevitable correction after four years of rapid ascent. But the markets, it turns out, were simply pausing for breath. On July 14th the price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate oil reached a new record in nominal terms of $78.40, although it has since fallen a little. Nickel followed, topping $26,000 a tonne for the first time. Even some agricultural commodities are starting to get caught up in the boom. Rapeseed oil, for example, is fetching unprecedented sums. The price of food crops has risen by 40% since the beginning of 2002, although that increase is dwarfed by huge run-ups in the prices of oil and metals, as the left-hand chart, below, shows.

The last two paragraphs here are a bit confusing, as the cycles referenced in the French study at first appear to be "super-cycles". But, upon closer inspection, the writer is ham-handedly making the point that the regular pattern of ups and downs in commodity prices over the last three decades has been broken in the last five years, perhaps auguring in a commodity "super-cycle" unrelated to anything in the French study. Some analysts believe that investors have inflated a speculative bubble in commodities. Hedge funds' investments in energy markets rose from $3 billion in 2000 to about $90 billion last year, according to the International Energy Agency, a think-tank. Trading of commodities at exchanges doubled between 2001 and 2005, according to International Financial Services London, an industry group. Over-the-counter trade has risen faster still.

Some analysts believe that investors have inflated a speculative bubble in commodities. Hedge funds' investments in energy markets rose from $3 billion in 2000 to about $90 billion last year, according to the International Energy Agency, a think-tank. Trading of commodities at exchanges doubled between 2001 and 2005, according to International Financial Services London, an industry group. Over-the-counter trade has risen faster still.

Other pundits think piling into commodities is justified, because the world has embarked on a “super-cycle”, in which commodity prices rise far higher and for much longer than is normal in a business blighted by frequent busts. The boom is certainly exceptionally long and lucrative. A recent report by Société Générale, a French bank, analysed five others since 1975. They lasted 28 months, on average, during which prices rose 35%. The present run, by contrast, has lasted 56 months, during which prices have doubled.

The super-cyclists put all this down to a simple mismatch between supply and demand. During the 1980s and 1990s, when commodity prices were low, mining and oil firms invested too little in new mines and wells, leaving them with little or no spare capacity. Although they are now rushing to increase their output, it takes years to find and develop new seams and fields. In fact, it takes longer now than it used to, because environmental regulations have become more onerous and activists more obstreperous around the world. With everyone trying to dig and drill at the same time, costs are rising and shortages of such things as huge tyres for mining trucks are hampering progress.

When the phrase commodity "super-cycle" is heard here, the chart below from Hot Commodities, by Jim Rogers, is more what comes to mind - to look at commodity "super-cycles", you have to go back before 1975.

They go on to talk about China, and the commodity demand generated by a nation of over one billion people, with its impact on the supply/demand dynamics for copper and other base metals. Many observers are still waiting for the Chinese economy to slow down, but it continues to roar along at official growth rates of around ten percent and whisper numbers still much higher.

Then, as always seems to be the case when the subject of commodities comes up, they start talking about gold. It's always interesting to read what economists have to say about gold.Gold is another exception. It is dearer than it has been for decades, yet jewellers and industrialists would need years to use up all the world's stocks. Gold is valued not for its scarcity, but as a hedge against inflation. Its price has duly risen, as worries about inflation have grown (thanks partly to the expense of oil) and central banks have raised interest rates. Higher interest rates, however, should eventually slow global growth, and so crimp demand for other commodities. The prices of gold and more mundane metals may therefore start to move in opposite directions.

Of course, you wouldn't expect an economist to say that the gold price is on an upward trajectory because the world, including many of its non-Western central banks, is increasingly distrustful of the world's paper money.

And then it's on to oil.Not even oil, the archetypal industrial commodity, quite conforms to the super-cycle theory. Granted, consumption continues to rise, especially in China, where imports have grown by about 10% so far this year. Furthermore, the industry can muster only about 1.5m barrels a day of spare pumping capacity—a tiny fraction of the 84m-odd barrels the world consumes daily. That makes the price sensitive even to relatively minor interruptions in supply. Iran, which exports 3.4m barrels a day, has threatened to use oil as a weapon in its disputes with America and the European Union. So oil traders twitch every time the two sides exchange barbs.

Well, the world will find out just how overvalued these commodities are - it is easy for an economist to calculate that oil is overpriced by 50 percent, but many have been predicting a return to $35 oil for the better part of a year now. Apparently the whole world has it wrong, and it is just a matter of time until the economists are proven right.

Nonetheless, during the past year spare capacity has actually increased marginally, as have stocks. This cushion should expand further over the next couple of years, as production starts from oilfields now being developed. Meanwhile, there are signs that demand, although not falling, is growing more slowly in the face of high prices. Supply and demand will certainly remain finely balanced for several more years, but the outlook is improving for consumers—even if this is not yet detectable in the price of oil.

It is hard, concedes Frédéric Lasserre, the author of Société Générale's report, to translate nebulous fears about future supply into prices. In the long run, the price of any given commodity should revert to the cost of producing an incremental unit of supply. By that measure, Mr Lasserre calculates, oil is overvalued by 50%, and zinc and copper by almost 40%. In the short term, the level of stocks plays an important part. But again, relative to the historical relationship between stocks and prices, Mr Lasserre reckons copper is 148% too dear; zinc, 122%; nickel, 70%; and oil, 49%.

Other analysts see parallels with the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s. After all, plenty of people are opining that “things are different this time”. Pension funds and individual investors are keen to get in on the action. CalPERS, America's biggest pension fund, is due to decide soon whether to put money into commodities. If such a conservative operator is eyeing commodities, cynics say, then a correction must be close at hand.

We will see.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

6 comments:

the US is a non-commodity(for the most part) economy. it growths BECAUSE commodities fall and slows when they rise. sure a global slowdown will hurt, but that will most likely cause a lower dollar, pushing up commodities denominated in dollars.

I think schiff had commentary on this.

Your last paragraph contains reasoning you have rejected before. Or could you imagine writing in the same tone:

Well, the world will find out just how overvalued ths commodity is - it is easy for me to calculate that housing is overpriced by 50 percent, but many have been predicting a return to 2003 prices for the better part of a year now. Apparently the whole world has it wrong, and it is just a matter of time until the I am proven right.

We will see.

Under different circumstances, I would have gone on at some length regarding the article's commentary on both oil and gold, but the activities of the weekend and the oppressive heat have drained most of my energy. I thought this was an interesting article because it represents current mainstream economic thought regarding commodities (which I think is wrong) and I was certainly being sarcastic when I said:

"Apparently the whole world has it wrong, and it is just a matter of time until the economists are proven right."

The housing analogy for 2003 is a good one, Mr. Gates, and makes me wonder why economists seem to be housing-friendly but anti-commodities...

Economists will always discredit a commodity bull market because it is evidence that their work to control prices (and not money supply) has failed.

economists have declared victory against inflation, so don't expect them to see a commodity bull market. they also have many years invested in the Federal Reserve being able to engineer the economy with interest rates. if there is a housing bubble, it falls squarely on the head of the economic establishment. a commodity bubble would a recognization that they failed and created so much money(they call it liquidity) they helped(but not essentially caused) and caused the commodity bubble.

Imagine an unregulated market in which a cartel of banking and financial interests are able to buy up paper contracts equal to four times the existing physical supply of a commodity and then raise the price 78 % in two months. All on borrowed money.

By extorting money from the physical buyers and short sellers, making them pay two or three times what the cartel payed to gain control of the market, the cartel makes back their initial investment in a few months selling paper, never taking control of the physical commodity. The rest is gravy.

This is how the futures market works. This is what is causing much of the inflationary spiral.

The US regulator, the CFTC, is week and incompetent, allowing this organized criminal behaviour to florish and persist. Some organization in London referred to as Los Banditos Muchachos or some such moniker controls over 50 % of the contracts in copper. The Chinese government is heavily involved.

wall street is up to their ears in this country. It's all fitting with the reign of GW and company.

Post a Comment