Oh, To Have Been a Fly on the Wall

Thursday, September 21, 2006

With another Federal Reserve policy meeting having come and gone yielding the same result as last month - a decision to leave short-term interest rates unchanged at 5.25 percent - you can't help but wonder about the content and the tone of the discussion as board members deliberated on the state of the economy and the future of U.S. monetary policy.

Yesterday's policy statement was little changed from last month, the most significant deviation being the glaring omission of the word "gradual" from the board's characterization of the housing market slowdown.

By no small coincidence, news also came yesterday that Countrywide, the nation's largest mortgage lender, is planning to lay off between five and ten percent of its workforce.

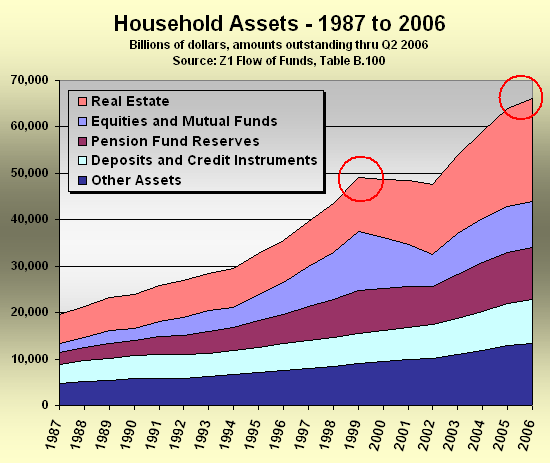

All this followed Tuesday's release of the Fed's quarterly Z1 Flow of Funds report that showed declining real net worth during the second quarter of the year.

While the minutes for yesterday's policy meeting will be released in about six weeks, it takes five years or more for the transcripts to become available. There were quite a few gems to be found when the 2000 transcripts were released earlier this year, that is, the last time that the western world was staring an asset bubble square in face wondering what it was going to do next.

For the next five years, one can only wonder what was said during yesterday's meeting.

Don't Look Too Closely

When viewed at a glance, the major economic indicators seem to paint a picture of reasonable health - employment growth is stable and both economic growth and inflation have moderated but remain at levels that, when viewed from a historical perspective, should be no cause for alarm.

Regarding consumer prices - not necessarily the ones that consumers actually pay, but rather, those that are tallied at the Bureau of Labor Statistics - the news is good. The decision to pause last month looks better with each passing day and the cacophony of questioning directed at new Fed Chair Ben Bernanke and his inflation fighting mettle has been largely silenced.

The lone exception to the now almost conventional wisdom that Ben Bernanke knows what he is doing is, of course, Jeffrey Lacker of the Richmond Fed. Mr. Lacker stood alone with his hand raised once again when they went around the room asking, "Who wants five and a half?"

After a mostly tame report on consumer prices last week, Tuesday's report showing falling producer prices (less food and energy), and with the cost of energy products plumbing multi-month lows, some of the discussion has now turned a full 180 degrees back toward the 2003-era "disinflation" ramblings, and yes, the possible return of an "unwelcome fall in inflation".

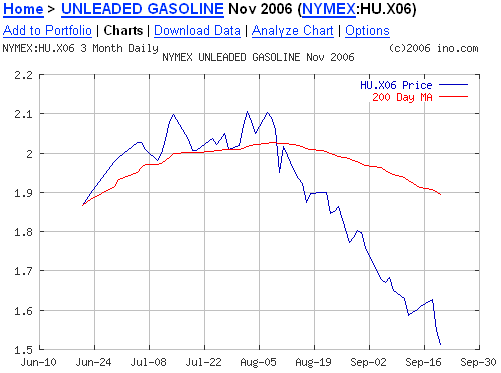

Plunging energy prices are going to wreak havoc with next month's inflation statistics and it should make for some intriguing commentary from the talking heads who will attempt to make sense of it all. The November futures contract for unleaded gasoline has dropped almost 30 percent in just over a month. It may take a little longer for retail gasoline prices to fall, certainly not adjusting as quickly as on the way up, but if current price levels are maintained for any length of time, or if they fall even further, then things will get interesting rather quickly.

It may take a little longer for retail gasoline prices to fall, certainly not adjusting as quickly as on the way up, but if current price levels are maintained for any length of time, or if they fall even further, then things will get interesting rather quickly.

Ben Bernanke will likely begin rummaging through his desk drawers searching for his now-famous 2003 paper, "An Unwelcome Fall in Inflation?"

A student of the Great Depression, he is superbly qualified to try his hand at maintaining some minimum level of currency debasement.

The Problem with Rising Asset Prices that Stop Rising

Most of the discussion at yesterday's meeting probably revolved around the housing market, hearings being held across town by the Senate Banking Committee presumably having been noticed by the staff at the Federal Reserve.

Last week, elected officials talked about the economic impact of the housing bubble and this week it was the risk of risky loans. It's not clear whether any solutions were found, or even if any problems have been identified, but by the look of the titles of the hearings, it sounds like they meant business:

Housing being a relatively slow moving asset class, government officials are in the potentially dangerous position of actually being able to take action while an asset bubble is still bulging on all sides, not yet sure if a slow leak or a more catastrophic outcome lay ahead, were it to be left alone to determine its own fate.

It seems that the inherent problem with an economy based on ever-rising asset prices is that eventually asset prices stop rising. Policymakers go along with easy money policies, allowing first stocks and now housing to rise at many times the rate of reported inflation, and then one day, the music stops.

The asset prices stop rising.

On the way up, shareholders, homeowners, and economists pat each other on the back, sure that they are blessed to be living in a new and different era where lunches are free and prosperity comes easy. This can continue for quite some time since rapidly rising asset prices are not deemed problematic unless and until adverse effects are felt on the broader economy - like in 2000.

One look at the chart below and it appears that another inflection point is nearing.  When equities reversed course back in 2000, real estate stood at the ready, waiting to be pumped up so that the good times could continue. Now that housing is in serious trouble, prices now declining in many parts of the country, it's not clear what asset class will take the baton next.

When equities reversed course back in 2000, real estate stood at the ready, waiting to be pumped up so that the good times could continue. Now that housing is in serious trouble, prices now declining in many parts of the country, it's not clear what asset class will take the baton next.

News that net worth adjusted for inflation actually declined in the second quarter is certainly not a promising development. This is especially worrisome since it covers the months of April, May, and June, back when there was still hope for a summer rebound in housing.

In the quarters ahead, there may be some real surprises in store regarding the nation's wealth as measured by subtracting the value of its liabilities from the value of its assets.

Household net worth declined in nominal terms for three years straight starting in 2000. Particularly problematic in this calculation is that asset prices can go up or down, sometimes dramatically, but in recent decades debt has known only one direction.

The housing market is clearly coming undone in a very big way and it holds the potential to cause much more harm than the stock market did six years ago. The Federal Reserve and other government agencies are surely aware of this downside risk, however, it's not clear what they'll be able to do about it.

They probably talked about it at yesterday's Fed meeting.

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

7 comments:

Tim -

I also looked at the FoF data yesterday and posted a link to some data analysis I did:

Flow of Funds Data

It shows how cash, equities and real estate have risen and fallen over the years as America's assets of choice...

adam

The bubble is now too big for the Fed to effectively mitigate. But, I can guarantee you one thing. They will first attempt to distance themselves from blame and then portray themselves as coming to the rescue.

It's just disgusting and reviling.

I was thinking the other day that we really need a CPI that includes only pure asset prices, and another CPI that includes instead the regular financing payments that people typically make on the underlying assets. So, the "asset-only CPI" would include home prices, auto prices, big-ticket retail items, etc. The "financing CPI" would be expressed purely in terms of the typical monthly cash-flow for these things, added to the basic needs that can't be financed (which could be considered an omnibus "basic needs financing" item that never goes away from the household budget).

While this might seem to complicate things, at least it disambiguates. The reason is that by conflating asset prices and cash flow, as in "owners-equivalent-rent" and so forth, the existing CPI confuses the secondary effects of interest rate rises with the primary effects of supply and demand on assets. That is, the Fed's own interest rate machinations presumably bear strongly on consumer cash flows due to financing (credit, adjustable mortgages), but more weakly on the underlying asset prices. How can the Fed really know when it increases interest rates whether the CPI is tainted with the effect of its own interest rate increases? It can't. The signal is polluted.

This is partially why I am suspicious that they really know what they are doing. It seems the "safest" way for the Fed to behave in the face of uncertainty is just to do whatever will please Wall Street today.

Maybe we need something that goes beyond the CPI... the "Consumer Cash Flow Index" that includes all forms of ongoing financing (student loans, credit card debt, etc). I suspect no one would like what they see if this was all added up, rather than the current practice of making an exception for housing just because mortgage financing allows for a downward CPI alteration.

Why don't we just let borrowers and lenders settle interest rates to their liking (i.e. the free market)? Why any central policy at all?

People to people lending has already begun

http://www.prosper.com/

Now, just get rid of the Fed.

If p2p banking gains traction, it will narrow the spread between lending and borrowing rates - cut costs to both. But to truly level the playing field with fractional reserve banks, you would have to remove their Fed safety net.

Post a Comment