Too Low for Too Long

Monday, November 06, 2006

"I am not a trained economist and make no pretense whatsoever of being a formal practitioner of the dismal science. "

That's not something that was said around here. That's what Richard "eighth inning" Fisher, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, had to say last week during a speech on the subject of Data Dependency.

He went on to explain how economics is not dismal at all and to describe the qualities that landed him the top post at one of the twelve Federal Reserve Banks.To me, "dismal" is a misnomer; economics is a vibrant and exciting field of study, especially in a capitalist society where it best applies itself to the conundrums of capital markets and the intricacies of monetary policy.

Mr. Fisher has always seemed a bit different than the other Fed heads, mostly as a result of saying things that others in his position would not dare. In mid-2005, he predicted the imminent cessation of rate hikes earning the moniker "eighth inning" for a baseball metaphor that proved far from the mark. I came to economics and the markets late in life. I started out as a midshipman at the Naval Academy, then migrated from learning to navigate the seas to navigating through the undergraduate basics of economics at Harvard. After a brief detour to Oxford—principally to find my wife and perfect my taste for good beer—it was onward to Stanford Business School, where I discovered what has become a lifelong passion, with its own branch of economics: decisionmaking under conditions of uncertainty.

I came to economics and the markets late in life. I started out as a midshipman at the Naval Academy, then migrated from learning to navigate the seas to navigating through the undergraduate basics of economics at Harvard. After a brief detour to Oxford—principally to find my wife and perfect my taste for good beer—it was onward to Stanford Business School, where I discovered what has become a lifelong passion, with its own branch of economics: decisionmaking under conditions of uncertainty.

For over a decade before I took up public service in 1997, I was able to profit from that passion as a hedge fund manager. Back in those days, the investors in funds actually made more than the managers of those funds—imagine that! Now I have the responsibility to apply what I have learned over the years in a different context—the making of monetary policy.

He was off by nine innings as it turned out (either that or he was counting on extra innings).

According to his bio, he founded Fisher Capital Management and a funds management firm, Fisher Ewing Partners, managing a fund called Value Partners that earned 24 percent per year under his watchful eye.

So he knows a thing or two about the real world and how imperfect it can be.

He also knows a thing or two about bad data, making headlines again last week when he criticized Alan Greenspan's interest rate policies of recent years, citing faulty inflation data.A good central banker knows how costly imperfect data can be for the economy. This is especially true of inflation data. In late 2002 and early 2003, for example, core PCE measurements were indicating inflation rates that were crossing below the 1 percent "lower boundary." At the time, the economy was expanding in fits and starts. Given the incidence of negative shocks during the prior two years, the Fed was worried about the economy's ability to withstand another one. Determined to get growth going in this potentially deflationary environment, the FOMC adopted an easy policy and promised to keep rates low. A couple of years later, however, after the inflation numbers had undergone a few revisions, we learned that inflation had actually been a half point higher than first thought.

Around here there is another word for what Alan Greenspan left behind - a "substantial correction" that is "inflicting real costs" is surely far too kind a characterization.

In retrospect, the real fed funds rate turned out to be lower than what was deemed appropriate at the time and was held lower longer that it should have been. In this case, poor data led to a policy action that amplified speculative activity in the housing and other markets. Today, as anybody not from the former planet of Pluto knows, the housing market is undergoing a substantial correction and inflicting real costs to millions of homeowners across the country. It is complicating the task of achieving our monetary objective of creating the conditions for sustainable non-inflationary growth.

We'll see how it all works out.

As to the question of inflation data, it's not often that you hear someone from the Federal Reserve say that inflation is higher than their statistics indicate, but that's what Mr. Fisher said about the 2002-2003 period. Upward revisions of a half point in the core rate of inflation, years after the fact, have cast a different light on the condition of the economy at the time.

This was back when phrases like "an unwelcome fall in inflation" were frequently heard and everyone prayed that dreaded "deflation" would not take hold.

Heaven help us if American consumers would ever come to expect prices to fall.

This is a core principle of the world's largest retailer and the basis for the entire Chinese export economy, yet "deflation" is a dreaded evil in economic circles.

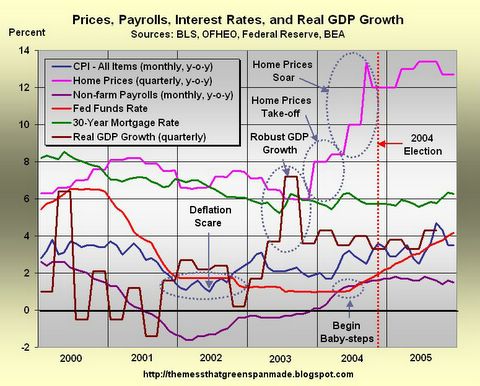

To help put that period into proper perspective, a chart from the Greenspan send-off provided here in January, Three Sins, One Gift - Sin #2 - Bending to the Will of Others, is reproduced below.

It's a rather busy chart, but one that nonetheless shows the myriad of factors that should have compelled the former Fed Chairman to ease up on the gas pedal a year or more before he did. There was an election coming up in 2004, and anyone with a conspiratorial bent would guess that all those visits to the White House in 2003 had something to do with the gas pedal getting stuck.

Beginning a sequence of quarter point rate hikes in June of 2004 has proved far too little, far too late - an error that was compounded by failing to provide any meaningful regulation of mortgage lending until just a month or so ago.

Greg Ip noted Mr. Fisher's speech in this story($) in the Wall Street Journal, taking the Dallas Fed President to task for breaking ranks by speaking out.In an apparent and rare in-house critique, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas said that because of faulty inflation data, the Fed kept interest rates too low for too long earlier this decade, fueling speculative housing activity.

If it weren't for the wholly unsound practice of creating so much money out of thin air, deflation wouldn't be such a bad thing. In the days when money was backed by something more than a government's promise, deflation was the natural result of improved productivity - when production became more efficient, consumer prices went down.

A number of critics have said the Fed under former chairman Alan Greenspan kept monetary policy too easy from 2003 to 2004. But Richard Fisher's remarks to the New York Association for Business Economics yesterday mark the first time some Fed watchers could recall a sitting Fed policy maker making such comments.

...

Mr. Fisher, who took office in April last year, said in an interview that his speech wasn't meant to be a criticism of the decisions Mr. Greenspan and the FOMC made then. He said: "I wasn't at the table at the time -- it's easy to look at things with 20-20 hindsight. The point is we need to continue to improve our ability to develop and work with better data."

Jan Hatzius, chief U.S. economist at Goldman Sachs, called Mr. Fisher's remarks "pretty striking," while noting it is Mr. Fisher's style to be opinionated. He added that while he agrees the Fed's policy from 2002 to 2004 fueled speculative housing-bubble activity, it was still reasonable "knowing what you knew at the time. You take out some insurance against a really bad, low-probability outcome, and after the fact you regret having paid the insurance premium."

Not a big deal.

Today, in a system that many characterize as "inflate or die", a generally falling price level can not be tolerated for fear of a calamitous outcome. Apparently the housing inflation that followed the bursting of the stock market bubble just a few years ago was the economy's latest reprieve.

With housing prices now spiraling downward, and the prospect of this spreading to the rest of the economy, the odds of new "deflation" warnings coming from the nation's central bankers increase by the day.

This is not a dismal science at all.

This is exciting - in the same sense that trying to catch a falling knife is exciting.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

5 comments:

Here's the WSJ article at a free site.

Tim,

You've hit the nail on the head with your observations regarding the benign nature of deflation -- for regular folks. Imagine an a world of gradually cheaper goods, more valuable earnings from year to year without getting a raise, and appreciating savings without "investing". This world existed in the United States before 1913.

For central planners and Wall Street, deflation (even gradual) is indeed deadly. Both love the automaticity of consumers borrowing, spending, and investing to an insanely exaggerated extent in the current system. They couldn't care less about the negative savings rate.

They've pulled off the whole scam pretty well (it required convincing the world that inflation was exogenous, rather than caused by the central planners and bankers themselves). The only hitch is that the resulting system is unstable and insolvent, as you do a great job of chronicling here.

Greenie's still talking:

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The U.S. housing market will weaken further, but the sharpest decline is over as inventories of unsold homes thin, Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said on Monday.

"This is not the bottom, but the worst is behind us," Greenspan said at a conference organized by financial services firm Charles Schwab.

--- so the worst is over, as in the "sharpest decline" is over --- prices could continue to go down for many, many years, according to this forecast --- he's still very good at obfuscation.

The Fed bubbles are far from over. The stock market is doing a NASDAQ.

Another fed sponsored bubble with an outsized downside. Wow ! You don't have to be a conspiracy wonk to judge this government out of control.

PS I wonder where the LME zinc stockpile has gone.

But Richard Fisher also said that this housing bubble is interfering with the ability of the fed to impliment monetary policy. In other words, the fed is wanting to crush inflation but cannot raise because that would crush the house bubble even more. I believe the housing bubble is toast, and that it doesn't matter. They may as well raise and get it over with.

Post a Comment