Think Like an Endowment

Friday, January 26, 2007

This story from The Economist explaining the superior investment returns earned by endowment funds should serve as a lesson to those who watch too much CNBC and are too enamored with the latest "system" to trade stocks.

What makes America's colleges such good investors?

A healthy portion of unconventional investments, a long-term strategy, and paying little heed to the advice offered by the faculty in their economics department are all key factors.AMERICA is the home of the efficient-market hypothesis, which says financial markets have become so keenly contested that it is impossible for investors to keep beating them. Yet the very universities that peddle this theory so confidently also gleefully undermine it by doing precisely that: over one year and over ten, their endowment funds beat the S&P 500 and hammer most other institutional investors, including pension funds.

Recall that Mr. El-Erian hails from PIMCO, the world's largest bond trading company, one of the first companies to provide a retail product in the commodities sector with their PIMCO Commodity Real Return fund (PCRCX).

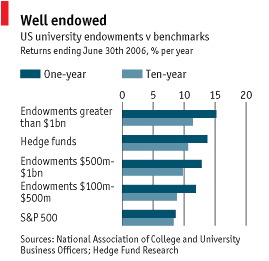

The final figures for the most recent fiscal year will be out next week. But according to preliminary numbers from the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and TIAA-CREF, a financial-services group, university endowments made an average return of 10.7% in the year to June 30th 2006, net of fees and expenses. The biggest endowments are big investors: between them, Harvard and Yale have some $50 billion, around one-seventh of the total. They tend to do better than their smaller peers and pretty much everyone else. Indeed, these eggheads even beat the quants. Endowments larger than $1 billion returned 15.2% on average last year, more than the main hedge-fund index (see chart). The best-performing endowment in 2005-06, which belonged to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, gained a handsome 23%. That put it a whisker ahead of Yale's (22.9%), run for more than 20 years by David Swensen.

The biggest endowments are big investors: between them, Harvard and Yale have some $50 billion, around one-seventh of the total. They tend to do better than their smaller peers and pretty much everyone else. Indeed, these eggheads even beat the quants. Endowments larger than $1 billion returned 15.2% on average last year, more than the main hedge-fund index (see chart). The best-performing endowment in 2005-06, which belonged to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, gained a handsome 23%. That put it a whisker ahead of Yale's (22.9%), run for more than 20 years by David Swensen.

Endowment managers would no doubt like to claim this is all down to skill. But they do enjoy certain advantages over their rivals. In principle, their investment horizon lasts not weeks, months or years, but forever. Their capital is extremely patient. Each endowment has a single client—itself—that needs to extract only a small sum annually to keep the wheels of scholarship turning. Therefore, unlike pension funds, they do not have to fret about matching assets with liabilities. This means endowments can tolerate lots of volatility, which in turn allows them to make, and stick to, contrarian bets. They have been “incredibly gutsy” in going against the grain, says Will Wechsler of Greenwich Associates, a financial-services consultancy. Perhaps they can stay solvent longer than the market can stay irrational.

A second advantage is the university environment. “Whereas pension trustees are naturally risk-averse, universities are all about innovating, financially as well as intellectually,” says James Walsh, who runs Cornell's $5 billion endowment. Investment constraints are kept to a minimum. Alumni with Wall Street experience are encouraged not only to donate money but also to sit on investment committees. Many are happy to oblige. “This gives us access to minds we couldn't otherwise afford,” says Mr Walsh. The brainpower on tap at the university itself is not always as useful. According to one former Harvard official, its endowment fund has done so well because it has avoided taking advice from the economics faculty.

Put these factors together, says Mohamed El-Erian, Harvard's endowment chief, and you have a recipe for “thinking more boldly than the pack”.

In September it was announced that the Harvard fund intended to increase their exposure to "real assets" by shifting another $1 billion into commodities - from an allocation of 13 percent to 16 percent of the fund.

While it is not known with any certainty, the Harvard fund likely utilizes a commodity investment approach similar to the PIMCO fund - commodity futures backed by inflation protected treasuries. This is the same approach now available to retail investors through a plethora of new commodity ETFs, the most recent additions being the seven funds launched earlier this month by PowerShares/Deutsche Bank:

In recent years, commodity investments have been a contributing factor in the superior performance of many endowment funds.America's endowments were among the first to look beyond the staid mix of domestic equities, bonds and cash. The idea they helped develop in the 1970s and 1980s—deemed eccentric at the time—was to break the portfolio into a mix of standard and “alternative” assets, as uncorrelated with each other as possible so as to spread risk. This strategy is sometimes referred to as “portable alpha”.

It's hard for most individual investors to go against the crowd.

Their early moves into hedge funds, venture capital, private equity, property, distressed debt and the like brought outsized profits. Universities and foundations have also benefited from geographical diversification, especially into emerging markets. Foreign equity was their best-performing asset class last year, making 24.7% according to a survey by the Commonfund Institute, which manages pooled investments. Endowments have also revolutionised commodities. By making a killing in “hard” assets like timber in recent years, the universities have helped to turn them from industrial assets to financial ones in investors' eyes. Harvard keeps three lumberjacks on its team, the joke goes.

Indeed, for university endowments to call all of these assets “alternative” is something of a misnomer. It is assets such as government bonds, once safely in the mainstream, that must fight for their place in university portfolios. Today the typical large endowment has 41% of its holdings in assets other than shares, bonds and cash, says NACUBO. In the past couple of decades, illiquid investments, which are less efficiently priced than liquid ones, have rewarded those brave enough to buy them.

There is sufficient quandary in managing a portfolio of your own without having to think about "alternative" investment classes. But, as demonstrated by the fund managers at Harvard and Yale, for those willing to go against the crowd, there are rewards.

Disclosure: The author is long PCRCX and DBE. He has no positions in any other stocks mentioned in this report.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

7 comments:

That's the great thing about investing for onesself: you have the option of acting much like a University endowment -- that is, if you don't fall for the CNBC crud.

It looks like oil and gold are about to finish up a pretty good week.

When's the next contest? Guess the mid-year prices of oil and gold?

Maybe I'll start one in March ending at mid-year as you've suggested - the last one was kind of fun.

"The Harvard Watch reports description of Harvard academics creating the public policy justifications for Enron's frauds while the Harvard endowment fed at the trough illuminated a perfect example of how the tapeworm gets the host to act against its own self-interest."

This is from:

http://carolynbaker.org/archives/catherine-austin-fitts-the-tapeworms-triumph-confronting-parasitic-corporate-underpinnings-of-the-us-empire

I guess I'm not surprised these endowments are doing so well.

From Ben Stein:

"(Another major source of Yale's great gains is their tax-free status. Its endowment managers can trade rapidly in hedge funds without paying the short-term capital gains rates that we peons pay. This gives them a big advantage over most investors. If it were taken away, I wonder what the endowment's return on investments would be in stock or commodities trading.)"

Thanks for the additional info anons.

good info from Ben Stein - he is growing on me - I only wish his parents had named him "Beer"

Post a Comment