Three Sins, One Gift - Sin #2

Thursday, January 29, 2009

This is part two in the series "Three Sins, One Gift" that is being repeated this week leading up to the three year anniversary of the retirement of former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan.

Original publication date: January 18th, 2006

----------------------------------------------------------

Sin #2 - Bending to the Will of Others

Early last year, Senate Minority Leader Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.) blasted Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, calling him "one of the biggest political hacks we have here in Washington." What could possibly have set Senator Reid off so?

Support for private social security accounts? Support for tax cuts?

"I'm not a big Greenspan fan", Reid said.

The outgoing Fed chair has been losing fans at a quickening pace as his retirement edges nearer and signs of a fading housing boom, the economy's life blood in recent years, continue to mount. Some of the criticism of Mr. Greenspan's tenure at the Fed involves the various opinions that he has offered - opinions generally in support of administration policies, from which he is supposed to be independent.

Some of the criticism of Mr. Greenspan's tenure at the Fed involves the various opinions that he has offered - opinions generally in support of administration policies, from which he is supposed to be independent.

Surely this was what motivated Senator Reid's objections.

It seems, over the years, Chairman Greenspan has been prone to bending to the will of others.

Founded in 1913 as a financially and politically independent agency, Federal Reserve Board activities were, from the outset, intended to be independent of political influence. Offering views on matters outside of the purview of monetary policy is something unique to Mr. Greenspan.

Serving in the position that many refer to as the second-most powerful in the United States, the views of a long-serving Fed Chairman carry an extraordinary amount of weight and can quickly shape opinions from Wall Street to Main Street to Capitol Hill.

With positions on tax-cuts that have adapted to each administration - in favor during the Reagan and Bush presidencies, opposed during Clinton's, and again in favor during recent years - he has at times sounded like a pitch-man for White House policies, though not nearly as boisterous a pitch-man as his counterpart at the Department of the Treasury, Secretary John Snow.

Alan Greenspan's seal of approval has been much more subtle.

Qualified with an extra key word or two that offer cover - "triggers" for tax cuts or "cautious, gradual" for private accounts - the Fed chair's endorsements of White House policies have been at the same time mildly ambiguous and tremendously powerful.

Long Ago, Before the Fed

Many years ago, shortly after Paul Volcker had hiked interest rates to near 20 percent to stave off roaring inflation (which at the time included actual home prices and not owner's equivalent rent), and after Mr. Volcker had received hundreds of sawed up two-by-fours from irate builders whose livelihoods he had affected, Alan Greenspan set out to save social security.

The Greenspan Commission on Social Security Reform resulted in the near doubling of the Social Security tax on working individuals. It resulted in a huge surplus in the Social Security Trust Fund as baby boomers were just entering their prime working years.

While ostensibly shoring up the system for future retirees, this move provided the added benefit of making available an annual stream of funds that could be borrowed as inter-governmental transfers, rather than via public debt offerings.

Borrowing from the Social Security Trust Fund, a practice that continues to this day, does not appear as part of the federal government's annual budget deficit.

This helped make Ronald Reagan's massive tax cuts for the wealthy much less noticeable than they would otherwise have been, and began the process of rapidly rising public debt.

Reagan appointed Alan Greenspan as Federal Reserve Chairman a few years later.

Charles Keating and Long Term Capital Management

Other examples of the malleable Mr. Greenspan are known - two more are recounted here, with some help from Devil Take the Hindmost, by Edward Chancellor (see this previous post for lengthier excerpts).

Before taking over for Paul Volcker in 1987, there was an intriguing crossing of paths between Charles Keating and Alan Greenspan in the mid-1980s. Recall that the last national real estate boom/bust occurred in the late 1980s, culminating in the Savings and Loan crisis a decade and a half ago.He [Keating] hired the economist Alan Greenspan, later Chairman of the Federal Reserve, to support Lincoln's application to increase its "direct investments" to more than 10 percent of assets. In a letter he must have come to regret deeply, Greenspan wrote to the California bank regulator that the management of Lincoln and American Continental was "seasoned and expert ... with a long and continuous track record of outstanding success in making sound and profitable direct investments."

And, after helping to save the world on a number of occasions in his first ten years on the job as Federal Reserve Chairman, when Long Term Capital Management wound up on the wrong side of an interest rate bet, Alan Greenspan was there once again.

In another letter dated 13 February 1985, Greenspan claimed that Keating's management had turned Lincoln into "a financially strong institution" which would not pose any risk of loss to the federal insurer "for the foreseeable future." Greenspan was paid $40,000 for writing the two letters and testifying on Keating's behalf.Among John Meriwether's partners was a former vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve named David Mullins.

In recent years, as the number of hedge funds has exploded and the notional amounts of derivatives has reached astronomical levels, Mr. Greenspan has continued to resist the regulation of hedge funds and derivative products.

Mullin's friend and former colleague Alan Greenspan was also embarrassed by events at LTCM. For several years, Greenspan had vigorously resisted calls to regulate both the derivatives markets and hedge fund activities. Only a couple of weeks before the bailout, Greenspan had insisted to Congress that hedge funds were, in his words, "strongly regulated by those who lend them money." Yet the leverage at LTCM showed clearly that this was not the case.

...

Shortly after the bailout of Long-Term Capital Management, Paul Volcker, Greenspan's predecessor as Federal Reserve Chairman, asked, "Why should the weight of the federal government be brought to bear to help out a private investor?"

...

A few years earlier, the Federal Reserve had passively stood by while Drexel Burnham Lambert, an investment bank with some five thousand employees and a history stretching back into the nineteenth century, was deserted by its envious Wall Street competitors and collapsed because of liquidity problems.

Long-Term Capital Management, on the other hand, a mere four-year-old upstart with only two hundred employees but partners and investors drawn from a cabal of finance professors, central bankers, and the cream of Wall Street, was considered more important than Drexel and simply "too big to fail".

On more than one occasion, he has marveled at their "risk spreading" qualities, integral to global finance today. Many wonder if another derivative crisis, similar to the LTCM melt down, is waiting for a precipitating event to set it off.

The White House Visits

Although it will likely never be known with any certainty what Alan Greenspan talked about during his visits to the White House during the first few years of the George W. Bush administration, it will not stop people from wondering about the possibilities.

A casual visitor during the Clinton years, both the frequency of visits and the choice of White House officials with whom he spoke, take on added significance when viewed through the lens of monetary policy actions in a struggling economy with a U.S. President clearly having set his sights on re-election.

Kenneth H. Thomas compiled the following data and additional commentary is provided about the Fed Chairman's White House visits from this post last year, over at The Big Picture.

In light of the tragic events of September 11th, surely increased coordination between the executive branch and the nation's central bank would seem warranted. Ensuring the stability of financial markets goes a long way in explaining the 2001 and 2002 visits, but the trend not only continued, but accelerated in 2003 and 2004.

Occurring at about the same frequency as during the Clinton years, visits to the White House Counsel of Economic Advisers were routine during the first few years of the Bush administration.

But the other visits were anything but routine.

Vice President Cheney tops the list with seventeen face-to-face sessions during this time, followed by 11 visits with Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, another 12 visits with Condoleeza Rice, and a few with Andy Card, Colin Powell, Paul Wolfowitz, and Scooter Libby.

It makes you wonder what they could possibly have talked about.

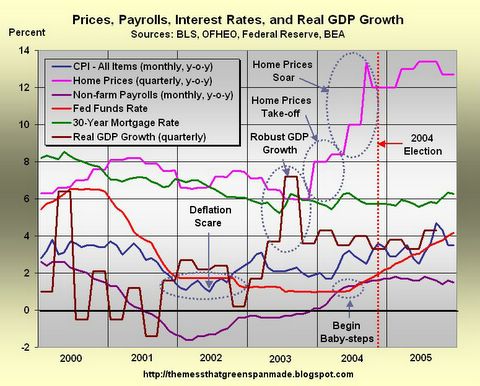

It makes you wonder if there could have been any impact on monetary policy. Maybe this chart will help to explore the possibilities:

Click to enlarge

Following a few quarters of negative real GDP growth and job losses in 2000-2001, the federal funds rate was moved below two percent in early 2002, where it remained for nearly three years - 2002, 2003, and 2004.

Given talk of deflation, and a clearly struggling labor market in 2002, this certainly seemed to be prudent action to take. The rationale for monetary policy during 2003 and 2004, however, is less clear.

Clearly, GDP growth rebounded in a big way during 2003, and the labor market was improving albeit slowly. The unemployment rate during 2003 averaged six percent, not far from the historical average, but it did begin declining rapidly at mid-year.

Inflation, as measured by the CPI-All Items index was above two percent again, and the housing market was appreciating at an annual six percent rate. What was the monetary policy response in 2003?

Rates were lowered from 1.25 percent to 1 percent.

Toward the end of 2003 and into early 2004, housing began to take off in a big way. Inflation was rising, employment was rising, and GDP growth was steady. What was the monetary policy response in early 2004?

Rates were held steady - the pedal was held firmly against the metal with short-term rates of one percent.

It was not until mid-2004, a mere six months before the 2004 Presidential election, that rates were nudged off of their rock-bottom position with the beginning of a long series of quarter-point baby steps.

By this time, home prices were rising at 8, 10, and 12 percent year-over-year, reported inflation had cleared three percent and was headed toward four, jobs were being created at a healthy clip, and Americans were discovering the joys of real estate speculation and home-equity withdrawal amidst the nirvana of rapidly rising real estate prices.

Then came the election.

It is likely that no one will ever know if or how the White House visits affected monetary policy during 2003 and 2004, but it won't stop people from wondering.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

1 comments:

"Many wonder if another derivative crisis, similar to the LTCM melt down, is waiting for a precipitating event to set it off."

We now know the answer to that one!

Post a Comment