More from The Economist

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

Three more very good stories from the Finance and Economics section of this week's The Economist. The Christmas cheer appears to have completely worn off now - an informal survey of the current issue reveals a distinctly dour view of many things American.

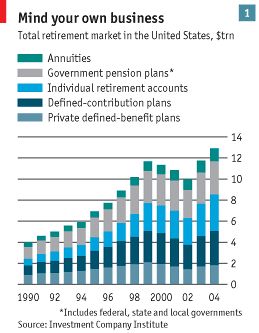

In Caveat investor, they wonder how all the traditional pension plans are going to fare, now that IBM has announced the end of their defined benefit plan, with more to follow (yesterday, Alcoa announced they were ending their defined benefit plan for new hires in March of this year).

Better financial education and stock markets that rise in perpetuity are the key, but, even with the so-called Freedom Funds (which are certainly a step in the right direction) it's natural to wonder if things really need to so complicated for your average worker.WHEN IBM announced an overhaul of its pension plan for employees in America last week, it joined a parade of employers that are shifting more responsibility for saving for retirement on to workers.

Pointing to record levels of homeownership may not be quite the indicator that Mr. Glassman believes, given the types of loans that are being made these days and the potential fallout from the U.S. housing bubble.

...

To the extent that this creates and encourages individual choice and responsibility, it is something to welcome rather than to fear. Many other countries, facing huge state-pension obligations, would also like to see their citizens assume a bigger role in providing for their own retirement. Even so, the trend raises an important question: how much do people due to take on these new responsibilities know about basic financial concepts?

The answer seems to be: not much, and less than they think they do. Studies show that many people overestimate their knowledge of everything from inflation to risk diversification and compound interest. One survey in Australia found that 37% of people who owned investments did not know that they could fluctuate in value. In America 31% did not know that the finance charge on a credit-card statement is what they pay to use credit.

...

Although education and sales are meant to be strictly separated, many of those giving the seminars work for firms that sell financial products. Some employers have been hesitant to sponsor financial seminars for fear of being sued, notes Lynn Dudley of the American Benefits Council, a lobby group. Two bills now before Congress attempt to deal with this question.

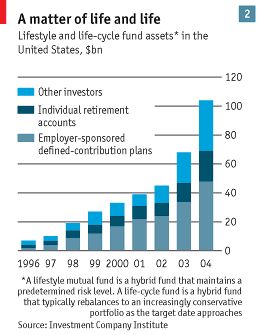

Meanwhile, a growing number of pension schemes offer “lifestyle” or “life-cycle” funds that skirt the question of advice by automatically shifting the mix of investments away from equities and towards bonds and cash as retirement nears.

...

Some dismiss worries about low financial literacy. “Complaints that people are too stupid to manage their own money are dead wrong,” wrote James Glassman, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, recently.

He points, for example, to America's record levels of home-ownership.

There is good reason to believe that people will learn if they want to and if they must. It is not so long since the go-go 1990s, when millions started investing for the first time. Many then learned painful lessons about the risks of overenthusiasm for equities. Perhaps a strong message is needed to get people saving now for retirement a few decades away. Ms Lusardi offers a suggestion: “Tell them, ‘you're going to be poor, it's going to be tough'. The mutual-fund companies show pictures of cruises. You've got to show a nursing home and they'll give it some thought. Tell them poverty at retirement is hell.”

The propect of learning from mistakes made first in stocks, then in housing, then in saving for retirement doesn't seem like a good long term plan - pictures of nursing homes and talk of poverty may be much more effective in coaxing spendthrift Americans to start saving again.

In The aggro of the agora ($), the consumer's ability to make sound decisions in a complex world is once again questioned. One suggested solution, to make things simpler as in the dentistry example, seems to be almost completely at odds with the desire of government and big business to make an ever-increasing number of choices available to consumers.“WE MUST accept the consumer as the final judge,” wrote Frank Taussig, a former president of the American Economic Association (AEA), in 1912. His view was once an article of faith of the economics profession: the consumer was sovereign, the market his servant. It fell to economists only to explain the consumer's decisions, not to second-guess them.

How about fewer choices? Some argue that people today are faced with an overwhelming number of choices in their everyday lives, the likes of which no previous generation has ever seen. Health care, retirement planning, tax planning, mortgage finance, credit cards, rebates, special offers, comparison shopping on the internet.

The AEA's latest annual meeting, held last weekend, made one thing abundantly clear: this ritual deference to consumer sovereignty is slipping.

...

Listening to Mr Campbell's AFA address, it is easy to conclude that agoraphobia reigns over the American housing market. Most American mortgages offer fixed interest rates, but can be refinanced without penalty should the household so wish. The steep decline in interest rates between 2001 and 2003 prompted many households to do just that. But a large fraction fell victim to inertia. In 2003, Mr Campbell estimates, most households were still paying interest at more than a percentage point above the market rate; an eighth were paying a spread of more than three points.

What to do? Mr Campbell is inspired by the example of dentistry. The big gains in oral health, he points out, stemmed from straightforward advice and easy-to-use products. Economists should promote the financial equivalent of brushing twice daily with toothpaste. Such simple, effective ideas are surprisingly rare in an otherwise competitive financial industry. Why, for example, does a mortgage lender not offer a fixed-rate mortgage that refinances automatically whenever the market rate falls too far below the rate the customer is paying?

Mr Campbell speculates that the agoraphiles profit at the expense of agoraphobes. Those households that do refinance their mortgage enjoy a better rate precisely because the remainder do not. As a consequence, lenders who wanted to introduce a self-refinancing mortgage would face a conundrum. Naive householders would benefit from such a product, but if they knew that, they would no longer be naive (and would not need it).

Mr McFadden takes all this a step further. The “consumer may need to be coaxed and wheedled into responding to market choices with sufficient diligence,” he says. For his predecessors, such as Taussig, this is heresy. The consumers' choices are the data—the given things—of economics. It is only by observing a consumer's choices that economists can infer his preferences. Thus to argue that we know what's best for consumers, independent of what they have chosen for themselves, is a failure of logic as well as the height of presumption. If our theory fails to explain their behaviour, it is our problem, not theirs. Mr McFadden seems tempted by the opposite conclusion. If economic theory fails to reflect consumer behaviour, perhaps consumers can be remoulded, better to serve the theory.

The failure of too much choice is best demonstrated by the new Medicare prescription drug plan. Increasingly, ordinary people are baffled at the array of decisions that they must now make, and many would prefer something simpler.

An abundance of choices seems to serve everyone well when the subject is something simple like laundry detergent, but when it's a question of health, or being able to put food on the table during their golden years, or even when buying a home, maybe fewer choices and more complaining would serve the public interest better.

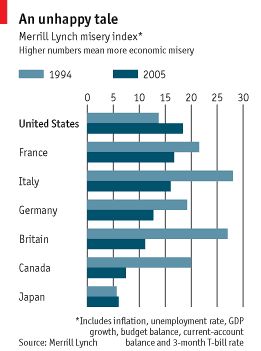

In Les misérables ($), it is learned that using an updated measure of the misery index, we Americans are the most miserable of the lot. That bit of news is certainly at odds with the chest thumping coming from the Federal Government and parts of Wall Street regarding the prospects for our purportedly robust economy.The misery index celebrates its 30th birthday. Time for a revamp?

It's about time somebody came up with a new misery index. It seems that the statistics that go into the original version - unemployment and inflation - have been so manipulated over the years that they have completely lost their original meaning.

IS THE economy in a better or worse state than ten years ago? The “misery index” (the sum of unemployment and inflation rates) is a back-of-the-envelope gauge of economic health. The higher the score, the greater the economic misery. It was invented by Arthur Okun, an American economist, just after the first oil crisis of the 1970s caused a sharp rise in both unemployment and inflation. Jimmy Carter popularised the misery index during his successful presidential campaign in 1976.

The classic misery index makes America's economy look pretty good, compared both with the past few decades and with much of Europe, burdened by higher jobless rates. But like many people when they hit 30, the index may be due for a spruce-up.

Merrill Lynch's economists have come up with a broader, international index. In addition to unemployment and inflation, it also adds interest rates and the budget and current-account balances, but then subtracts GDP growth (a good thing). In other words, the index not only reflects how cheery an economy feels today, but, by including budget and external balances, it also captures the ability of a country to sustain its merriment. For example, a large budget deficit probably implies higher taxes in future.

This new index could wipe the smile off the faces of exuberant Americans. The United States has the highest score (see chart), ie, it has the most wretched economy among the big G7 countries, thanks to its huge deficits. In the 1990s, by contrast, before its imbalances exploded, its index was one of the lowest. The United States is the only country to have seen a large increase in its misery index over the past decade. Virtually all the other G7 countries—including Europe—have seen sizeable improvements.

Japan, after a decade of woe, is now back to where it was in 1994. However, Japan's misery index is somewhat misleading, since, in effect, it treats deflation as good, not bad.

The superstar that deserves to smile is Canada. Over the past decade it has seen the biggest reduction in its misery index of any G7 economy. It is the only country running both current-account and budget surpluses—in happy contrast to its southern neighbour.

Now they should add in really important things like consumer indebtedness and retirement savings and see how we fare.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

4 comments:

The misery index thing is really fascinating. It would jibe with the claim that we are "doing well" by the usual, bulk econometrics, but that an increasingly skewed distribution of real wealth is actually putting most people in the squeeze.

I don't really agree with the "too many choices" thesis, however. I think more choices and more information are always good: its merely a matter of having the right cultural conditions to use them wisely and optimally. Americans have been told for years not to worry about their retirement (itself a relatively new concept), and only in the present is the opposite admonition beginning to dominate. There will be a cultural adjustment period.

I, for one, don't want my options reduced because there are irresponsible people out there.

By the way, the internet is emerging as a great tool for slicing through an otherwise bewildering array of choices in the market.

Aaron,

I suspect the vast majority of people reading this blog are fine with the number of choices available to them in their lives - I know I am. This comment was directed more toward the people who would find this blog to be completely incomprehensible. It never ceases to amaze me how un-informed or ill-informed people are about basic things having to do with their financial future.

As far as Canada goes, the average canadian is so miserable right now they seem prepared to rid themselves of a financially prudent, if scandal prone, government in favor of an american conservative open and honest government. I think a little misery is a good thing sometimes, obviously my countrymen have had it too good lately. The grass must be greener in the states, it has to be, it reeeaaallly has to be.

Sure makes the future look bleak for many folks!

Post a Comment