Commodity Inflation

Monday, April 17, 2006

This story($) from The Economist once again demonstrates the difficulty that dismal thinkers around the world are having trying to convince others that their definition of the word "inflation" is the correct one. While the makers of monetary policy view "inflation" through the lens of tortured statistics published by data collectors shopping for consumer items on behalf of their government, others contend that the supply of money and credit is a better definition of the word.AT FIRST glance, it has the hallmarks of a classic inflation scare. In the past week commodity prices—from oil to orange juice, silver to sugar—have reached eye-popping levels. In nominal terms, the prices of Brent crude, copper and zinc have hit record highs. Gold has topped $600 an ounce for the first time since 1980 and silver is at its dearest in a generation. Meanwhile, long-term nominal bond yields in America and elsewhere have risen to levels not seen in more than a year. On April 7th the yield on America's 30-year long bond climbed the 5% barrier, sending a flutter of fear through global markets. The ten-year yield may soon follow.

You see, unlike the 1970s, there is very little "inflation" today - except of course in housing, commodities, health care, and various other goods or services that don't originate in China or India. We live in a near perfect world of non-inflationary growth, and seemingly boundless wealth and endless prosperity (along with piles and piles of debt).

The rising costs of money and raw materials took leading roles in that economic horror movie, the 1970s, when inflation ran amok and growth froze. Once again, the two are connected, but in ways that are almost opposite to the ghastly stagflation of the past. If there is any common thread linking rising bond yields and commodity prices today it is not inflation, but growth—though there, too, the relationship is likely eventually to break down.

And as long as those soaring commodity prices don't pass through into "core inflation", there is no reason why this can't continue indefinitely.

So, how does one economist at The Economist explain the high commodity prices? It's really just a story of underinvestment and robust global economic growth, having nothing to do with the declining purchasing power of money.The commodities boom began in 2003, as China sucked in materials from Middle Eastern oil to Chilean copper. The demand followed a long period of low investment by commodity producers, which exacerbated the sense of a squeeze. This had some curious consequences: in Britain, manhole covers were stolen, melted down and shipped east (tabloids called it “the great drain robbery”).

Why does no one else seem to be bothered by the constant repetition of this "inflation expectations" argument?

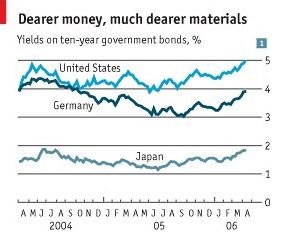

Meanwhile, despite healthy growth in the world economy, long-term interest rates seemed stuck. Alan Greenspan spent his last year at the Federal Reserve intrigued by the “conundrum” of why long-term bond yields weren't increasing, even as he and his colleagues were pushing up overnight rates to cool their economies. He left before the riddle could be solved. Now an answer is emerging (see chart 1). Since the turn of the year, the yield on ten-year Treasuries has climbed to its highest level since the Fed started tightening in June 2004. The yield on ten-year German bunds is near a 17-month high. Japanese government bonds have been yielding more than at any time for nearly two years. But by historic standards yields are still low. And the component attributed to expected inflation, measured by subtracting inflation-linked yields from nominal yields, is even less threatening. It has barely budged this year. In America it hovers around 2.5%, in Europe just above 2% and in Japan below 1%—roughly where it has been for two years, even as oil and other commodities have gone ballistic.

Now an answer is emerging (see chart 1). Since the turn of the year, the yield on ten-year Treasuries has climbed to its highest level since the Fed started tightening in June 2004. The yield on ten-year German bunds is near a 17-month high. Japanese government bonds have been yielding more than at any time for nearly two years. But by historic standards yields are still low. And the component attributed to expected inflation, measured by subtracting inflation-linked yields from nominal yields, is even less threatening. It has barely budged this year. In America it hovers around 2.5%, in Europe just above 2% and in Japan below 1%—roughly where it has been for two years, even as oil and other commodities have gone ballistic.

You start with inflation-indexed bonds, where the yield is calculated using a highly suspect (to put it nicely) consumer price index figure. Then you compare this yield with the same duration bond without the inflation protection (whose behavior no one has been able to explain in recent years - the "conundrum") and you conclude that "inflation expectations" are benign?

A classic case of two wrongs making a right or two uncertainties making a certainty, if there ever was one, but something that somehow still soothes the nerves of the dismal set as they continue to offer an ever-increasing number of explanations for why so many items not included in the price indices are rising at rates last seen when Saturday Night Fever was playing at local theaters.

Again, remember, rising commodity prices and "inflation" - two separate things.

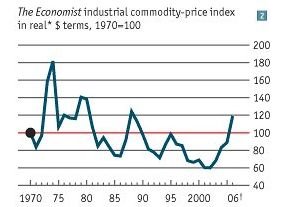

Economists, and central bankers in particular, must live in a sort of parallel universe where things are not as they seem, but as they say. Gasoline and heating costs may not seem like inflation when you live in this parallel "core inflation" world where food and energy and housing costs don't count, but ask someone who lives in the real world how three dollar a gallon gas feels when they fill up their Escalade and how they are coping with their adjustable rate mortgage payments for that ridiculously overpriced house they bought a couple years ago. There are plenty of reasons why hot commodity prices have not caused too many worries about inflation. One is that markets are confident that central banks will act to contain inflationary pressures. A second is that cheap Chinese exports have held down global prices. Another is that manufacturing's share of the world economy is declining; another is that the intensity with which industry uses raw materials is also shrinking—thinner steel in cars, for example—so that commodities' importance to inflation has diminished. And in real terms commodity prices are still well short of their 1970s peak (see chart 2). They have been on a downward trend since the 19th century, punctuated only by wars and other supply shocks: producers have generally coped with periods of surging demand, and probably will do so this time.

There are plenty of reasons why hot commodity prices have not caused too many worries about inflation. One is that markets are confident that central banks will act to contain inflationary pressures. A second is that cheap Chinese exports have held down global prices. Another is that manufacturing's share of the world economy is declining; another is that the intensity with which industry uses raw materials is also shrinking—thinner steel in cars, for example—so that commodities' importance to inflation has diminished. And in real terms commodity prices are still well short of their 1970s peak (see chart 2). They have been on a downward trend since the 19th century, punctuated only by wars and other supply shocks: producers have generally coped with periods of surging demand, and probably will do so this time.

And confidence in central banks to contain this non-existent inflation without destroying everything that Anglo-Saxons know to be good and true in this world - the value of their home? The same central bank that has been blowing serial asset bubbles of every greater magnitude with increasing potential for financial disaster?

Surely someone else is to blame for these soaring commodity prices and the stewards of the world's paper money are not responsible. Who could that be?

In the continuing stream of rationalizations that economists are now required to recite just to get through the day, the rise of commodity prices we now learn is being increasingly driven by speculators - and the worst kind of speculators - pension fund speculators.

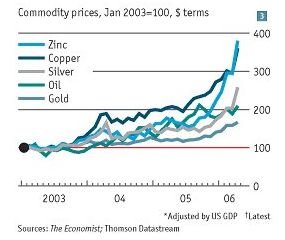

There is also a speculative side to the frothiness in the commodities market, which has grown since the rally started (see chart 3). As pension funds seek new sources of returns, some—such as the giant California Public Employees' Retirement System, with assets of $200 billion—are expected to dip their toes into commodities futures. In Britain J. Sainsbury, a supermarket chain, said it would choose commodities for about 5% of its fund, worth more than £3 billion ($5 billion) in all. Adding to the demand, the listing this year of exchange-traded funds in gold and other commodities has made life easier for would-be speculators. They don't even need to buy gold bars any more.

The cheapness of money has helped to feed investors' appetite for assets of all sorts—the ubiquitous “search for yield”. The rewards from investing in commodities have so far been extremely juicy.

You see, these pension fund managers are not out to preserve the value of the retirement savings of those workers contributing a portion of their hard earned wages in hopes of enjoying a few golden years later in life - these pension fund managers are just speculating.

But not to worry, the bond vigilantes are back.Now bond yields have at last begun to rise, sending returns for bond and commodity investors in opposite directions. The global economy is hot, which requires higher interest rates. To a certain extent, the rise in bond yields is a return to normality after the curious period when they failed to respond to tighter monetary conditions. This is no “debacle”, says Tim Bond, fixed-income strategist at Barclays Capital. “Things are safe and comfortable in the bond market at the moment.”

OK, a fixed income strategist whose name is Bond. Please. It's well past the first of the month. The "safe and comfortable" comment would have been much more reassuring if it hadn't been followed by "at the moment".

But whereas in the past higher commodity prices spelled bad news for bond markets, now the shoe may be on the other foot. Few expect that higher long-term interest rates will halt global economic growth, but they probably will have a dampening effect. That in turn should restrain demand for commodities.

Meanwhile, with yields rising, bonds will also compete with commodities for investors' funds, as they have with other risky assets, such as the Icelandic krona and the New Zealand dollar. With investors chasing commodities as if they were buried treasure, the danger is that returns will be even harder to find.

Anyway, there may be some truth in the idea that U.S. Treasuries at five percent are going to slow growth and reduce demand for commodities, however, interest rates will have no effect on the supply side of the commodities equation, which appears to be the more interesting side at the moment.

Five percent long bonds are not going to discourage too many pension fund managers from putting money down on the new commodity ETFs now that they have a taste of these returns, and the comparison to Iceland and New Zealand currencies is really not a fair comparison - that's just another form of paper that can be created and destroyed with the stroke of a keyboard.

As more and more people are learning, commodities are different. Economists will probably be the last ones to figure it out.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

7 comments:

If the economy tanks, where's all the money to keep pushing commodities and gold prices higher going to come from? Or will it just keep going up indefinitely, swallowing up capital?

Funny they should mention Iceland and New Zealand, as Stratfor just published an article a few days ago entitled "Global Economy: Canaries in the Coal Mine?"

"Against a backdrop of strong global growth, two small Western economies have hit upon hard times: Iceland and New Zealand. Their experiences, in the context of their geography and financial characteristics, could be heralding the onset of a fresh global financial crisis..."

I'd post the whole article, but it is subscriber-only. The gist of it was that these two economies are small, healthy, modern and devoid of corruption, yet their currencies and economies are getting crushed by an outflow of speculative capital that had flooded in over the last couple of years looking for high-yield, low-risk returns. This has left massive current account defecits (greater than that of the U.S. as a precentage of GDP), record interest rates and collapsing asset prices (including - you guessed it - the until-recently booming housing markets).

Their prediction is that similar countries that have no commodity exports to speak of will also be hit hard next: "Israel, Malaysia, Taiwan, Romania, Croatia, Bulgaria and perhaps Chile, Hong Kong and Thailand."

FWIW, here's the link.

I realized a few days ago that if you look at gold futures prices, which seem to have a predictable time premium, something north of 6% inflation is being priced in.

I would love to see the inflation deniers explain this. Why would a non-consumed commodity like gold have a time premium? The only explanation is that the value of the benchmark currency is expected to change predictably over time.

The interest rate argument in favor of bonds - the cry of the truly desperate. I laugh every time I hear it for bonds and for currencies. I can't believe any real fixed income expert actually believes that nonsense.

You start with inflation-indexed bonds, where the yield is calculated using a highly suspect (to put it nicely) consumer price index figure. Then you compare this yield with the same duration bond without the inflation protection (whose behavior no one has been able to explain in recent years - the "conundrum") and you conclude that "inflation expectations" are benign?,

Don't they use TIPS to figure out inflation expectations? I believe TIPS are indicating expectations about where they say they are (around 2.5%).

Whoops. I think I see what you're saying. That the TIPS-indicated expectations are inaccurate because the CPI is suspect?

How these fed heads like Yellen can come out with a straight face and say inflation is not a worry now or in the foreseeable future is sickening. The brainwashing of the american public is proceedeing at an even more rapid pace with Bernake in charge. All is well, keep spending, no inflation here. It is clear that the fed is deperately trying to keep inflation perceptions in check by focusing on the "core" rate while the cost of living for the average American skyrockets.

Post a Comment