Irrational Exuberance, Ten Years On

Thursday, December 07, 2006

In recalling the now famous speech given ten years ago on Tuesday, it's natural to wonder what the world would be like today if former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan had taken a different course of action after wondering aloud whether all the fuss with the stock market wasn't just another bit of, well, irrational exuberance.

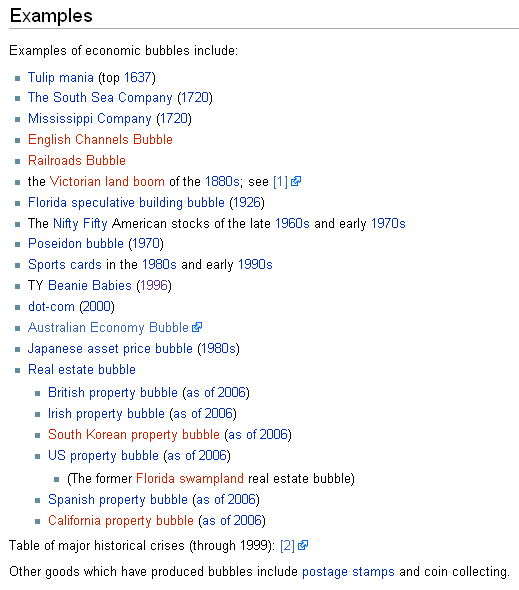

Through history, financial manias and bubbles have been common - tulips in Holland, the South Sea bubble, the Mississippi scheme, and the 1926 Florida real estate bubble, to name just a few.

While it's impossible to know what would have transpired had the monetary clamps been applied ten years ago, perhaps one of the best ways to assess what really did happen is to look up "economic bubble" at Wikipedia: Quibble if you will about what constitutes a "bubble", but without question, there have been an ever-increasing number of events with "bubble-like" characteristics in recent years.

Quibble if you will about what constitutes a "bubble", but without question, there have been an ever-increasing number of events with "bubble-like" characteristics in recent years.

Surely, ten years ago at age 70, the Fed Chairman had been around long enough to know what might result from his neglect of (and then cheerleading for) the rise in equities.

You didn't have to look very hard to see the signs of exuberance at the time. The speech was made after two years of hefty gains in the S&P 500 - over 30 percent in 1995 and over 20 percent in 1996.

Wasn't that enough?

Following are a few excerpts from the now famous speech that began with a lengthy stroll through history. Like Ben Bernanke, the former Fed chairman has a great appreciation for the past as well as a deep understanding of money, prices, and the role of the Federal Reserve.For, at root, money--serving as a store of value and medium of exchange--is the lubricant that enables a society to organize itself to achieve economic progress. The ability to store the fruits of one's labor for future consumption is necessary for the accumulation of capital, the spread of technological advances and, as a consequence, rising standards of living.

About five pages later we are back in the 1995 and the discussion turns to the difficulty in measuring prices and the rising price of assets.

Clearly in this context, the general price level, that is, the average exchange rate for money against all goods and services, and how it changes over time, plays a profoundly important role in any society, because it influences the nature and scope of our economic and social relationships over time.

It is, thus, no wonder that we at the Federal Reserve, the nation's central bank, and ultimate guardian of the purchasing power of our money, are subject to unending scrutiny. Indeed, it would be folly were it otherwise.

...

After the Civil War, redemption of the paper greenbacks issued during the war brought an era of a gold-standard-induced deflation, which, while it may not have thwarted the impressive advance of industrialization, was seen by many as suppressing credit availability for the rural interests of the nation, which were still a majority. The general price level declined for more than two decades, which meant borrowers were paying off their loans in more expensive dollars than those they borrowed.

...

Even with a central bank, the gold standard was still the dominant constraint on the issuance of paper currency and the expansion of bank deposits. Accordingly, the Federal Reserve was to play a minor role in affecting the purchasing power of the currency for many years to come.I doubt the tasks will become any easier for the Federal Reserve as we move into the twenty-first century. The Congress willing, we will remain as the guardian of the purchasing power of the dollar. But one factor that will continue to complicate that task is the increasing difficulty of pinning down the notion of what constitutes a stable general price level.

It is clear from the last few paragraphs above that the Fed chairman was struggling with the whole idea of measuring prices and monitoring asset values. The Fed's take on collapsing asset bubbles is defined here as well - they "need not be concerned if a collapsing financial asset bubble does not threaten to impair the real economy".

When industrial product was the centerpiece of the economy during the first two-thirds of this century, our overall price indexes served us well. Pricing a pound of electrolytic copper presented few definitional problems. The price of a ton of cold rolled steel sheet, or a linear yard of cotton broad woven fabrics, could be reasonably compared over a period of years.

But as the century draws to a close, the simple notion of price has turned decidedly ambiguous. What is the price of a unit of software or a legal opinion? How does one evaluate the price change of a cataract operation over a ten-year period when the nature of the procedure and its impact on the patient changes so radically. Indeed, how will we measure inflation, and the associated financial and real implications, in the twenty-first century when our data--using current techniques--could become increasingly less adequate to trace price trends over time?

So long as individuals make contractual arrangements for future payments valued in dollars, there must be a presumption on the part of those involved in the transaction about the future purchasing power of money. No matter how complex individual products become, there will always be some general sense of the purchasing power of money both across time and across goods and services. Hence, we must assume that embodied in all products is some unit of output and hence of price that is recognizable to producers and consumers and upon which they will base their decisions. Doubtless, we will develop new techniques of price measurement to unearth them as the years go on. It is crucial that we do, for inflation can destabilize an economy even if faulty price indexes fail to reveal it.

But where do we draw the line on what prices matter? Certainly prices of goods and services now being produced--our basic measure of inflation--matter. But what about futures prices or more importantly prices of claims on future goods and services, like equities, real estate, or other earning assets? Are stability of these prices essential to the stability of the economy?

Clearly, sustained low inflation implies less uncertainty about the future, and lower risk premiums imply higher prices of stocks and other earning assets. We can see that in the inverse relationship exhibited by price/earnings ratios and the rate of inflation in the past. But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade? And how do we factor that assessment into monetary policy? We as central bankers need not be concerned if a collapsing financial asset bubble does not threaten to impair the real economy, its production, jobs, and price stability. Indeed, the sharp stock market break of 1987 had few negative consequences for the economy. But we should not underestimate or become complacent about the complexity of the interactions of asset markets and the economy. Thus, evaluating shifts in balance sheets generally, and in asset prices particularly, must be an integral part of the development of monetary policy.

Well, they probably should have been concerned - if not in 1996, then certainly a few years later. At the time, the internet as we know it was being born and technology was changing at a pace set to accelerate in the years ahead. Pioneers like Mosaic with their nascent browser software would revolutionize the world of computers and communication and it's easy enough to look back and think that something could have been done to slow things down - at least a little bit.

At the time, the internet as we know it was being born and technology was changing at a pace set to accelerate in the years ahead. Pioneers like Mosaic with their nascent browser software would revolutionize the world of computers and communication and it's easy enough to look back and think that something could have been done to slow things down - at least a little bit.

So what if some start-ups couldn't be funded because money just wasn't available? Investors would have complained that money was too restrictive and that growth was being hampered - the absence of such complaints are characteristic of the recent era.

Monetary conditions in the last twenty years, and in particular in the last ten years since this speech, have been nothing other than easy. Money is now created, borrowed, invested, and lost with such casualness that most octogenarians, still mindful of harder times early in the last century, probably wince when they think about it.

Perhaps the former Fed chairman can be given a pass for his role in the late 1990s technology boom that went bust, but not so for what happened afterward - one look at the list of "economic bubble" above bodes ill for stability in the future.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

10 comments:

The most important sentence in the whole speech:

"Inflation can destabilize an economy even if faulty price indexes fail to reveal it."

Uh-oh!

Check out this bubble bust graph:

http://www.ernharth.com/2006/12/06/no-housing-bubble-really/

There was a recent WSJ op/ed on this by Jeremy Siegel who argued that the market was not really overvalued in 1996 and even after 1998 the tech stocks were the only ones overvalued. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB116537283751041900.html?

The article, and a spirited discussion of Mr. Sigel's findings can also be found here: http://socialize.morningstar.com/NewSocialize/asp/FullConv.asp?forumId=F100000015&convId=188867

We'll see how they feel about assets once we have another 30's style crash.

I actually think Greenspan genuinely thought he was staving off an asset bubble (specifically, in the stock market) in 1995/96 by keeping interest rates high. What he didn't realize was Japan's new ZIRP would send trillions of liquidity into the US economy (both as native Japanese investment and carry-trading), seeking higher returns in the US, founded on the interest rate differential. He also seemed ignorant as to the Fed's own loosening of the liquidity constraints in the early 90s, which made interest rates irrelevant as a governor on the extension of credit.

I actually think the market in 1995/early 96 was perfectly valued, compared to history. Just look at a chart of the inflation-adjusted Dow.

But there was definitely a lot of butt-covering in Greenspan's speech of the time. It really isn't that hard to measure the CPI: what matters is being honest and consistent about representing the cost of living (not some vague notion of the "standard of living"). Similarly, it isn't that hard to identify an asset bubble: compare the growth of asset prices to measurable fundamentals, the divergence is likely due purely to artificial market action.

I don't know about the fact that a greater number of asset bubbles being a 20th century phenomenon. Since the first cavemen realized that flint was an economic resource, there have been asset bubbles. Believe it or not, but the "deflationary" period of the 19th century was FULL of asset bubble. The railroad bubble. The whale oil bubble. The first panama canal.

Starting in the 1920's, debt has been seen as the panacea to people's problems. Greenspan's policies just made it worse, and our federal and state governments set bad examples by borrowing money against future returns (instead of doing it the hard way raising taxes and lowering services). Debt has been seen as not being a big deal. Go into default? Just declare bankruptcy! Or, use derivatives as "default insurance". Moral Hazards are being created left and right. This just allows bubbles to be blown bigger, as financial bubbles are a part of the human experience. See Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, that book has been around for more than a century and a half.

Robert Shiller's book of famous title which just HAPPENED to come out with impeccable timing was based upon his work which was originally published in 1996:

http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/peratio.html

His conclusion: "It appears that long run investors should stay out of the market for the next decade."

On July 1, 1996, the S&P 500 Index was 671. Today, a "decade" later, the S&P Index closed at 1,410 (dividends not included).

In my judgment it is certainly true that the measurement of inflation is deeply flawed. It is flawed not only in the valuation of services, as Greenspan mentioned, but also the way in which housing costs are figured. The key risk or high and/or rising inflation, is that income which is not spent as soon as it is earned, loses its purchasing power. Now poor folks always spend everything they earn. Really rich people could not spend it all even if they tried. But middle class people have a choice. Now people with reasonable incomes do not go out and save a part of their income for significant periods ( several years ) to buy groceries or clothes or DVDs. They do it to mainly to buy homes, and to save for retirement. It is very difficult to sustain the assertion that inflation is very low ( 2% ) when the cost of homes was increasing around 15-20% a year, until very recently, and had done so for 5 or 6 years. Any middle income person stoopid enough to have been saving a substantial downpayment on a home during the past decade would have experienced a massive erosion in the purchasing power of their savings. The same thing happened 15 years ago when Greenspan cut interest rates after the 1987 stockmarket crash.

ferromancer:

There will always be bubbles as long as there is herd mentality.

The question is whether it will be amplified by structural design of the government and financial system.

Post a Comment