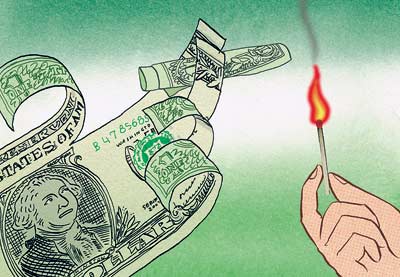

Playing with Fire

Monday, May 22, 2006

It is understandable that in uncertain times, writers at the venerable Economist magazine may occasionally peruse the fare over at the Prudent Bear website - it's a bit surprising though when they begin a story($) with a quote from a guest commentary.

What might they think of the monetary policy commentary appearing there now?

In last week's Finance and Economics section, one economist at the Economist took note of the growing number of writers comparing today's economic conditions with those of 1987.PrudentBear.com, a website that attracts the Jeremiahs of financial markets, carried a bleak commentary on the dollar on May 11th, laced with foreboding about American trade data, due the next day. “Can there be any doubt that the nation's record current-account and trade deficits have begun to take a serious and growing toll on the dollar? I think not.”

Many would have you believe that, having survived over 100 days now at the head of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke has avoided the curse of the new Fed chairman, since Alan Greenspan was at the helm not more than two months when the wheels temporarily came off in the middle of October 1987.

The writer, an American financial consultant named Douglas Gillespie, went on: “I remind readers that the stockmarket crash in October 1987 began months earlier as a dollar problem, that then became an interest-rate problem, that then became a stockmarket problem—a very, very big stockmarket problem!” As it happened, the next day, May 12th, the dollar's broad trade-weighted index plunged to its lowest level since 1997. In the next few days, the dollar was followed downwards by the prices of all sorts of assets, including shares, bonds, gold, industrial metals and oil.

As it happened, the next day, May 12th, the dollar's broad trade-weighted index plunged to its lowest level since 1997. In the next few days, the dollar was followed downwards by the prices of all sorts of assets, including shares, bonds, gold, industrial metals and oil.

After a steadier couple of days, more trouble landed on May 17th in the shape of poor inflation data. America's “core” consumer-price index, which excludes food and energy prices, rose by 0.3% in April. Bond yields rose a bit, as you might expect, but the stockmarket took a pasting: down went the S&P 500, by 1.7%.

...

Worse still, some (and not just bears such as Mr Gillespie) saw what Richard Cookson, of HSBC, a big bank, who is a former Economist journalist, called “echoes of 1987”. So far, as Mr Cookson pointed out, it is hard to argue that financial conditions are anything like as severe as those leading up to that year's stockmarket crash. But just as it did then, much depends on how policymakers handle the slippery dollar and jumpy inflation. Leading that effort is Ben Bernanke, chairman of America's Federal Reserve, who is as untested in coping with macroeconomic disturbances as Alan Greenspan was when he took over the central bank two months before the stockmarket crash in October 1987.

From the point of view of equities, however, the period of the Vietnam War may be a more appropriate comparison.

Recall that back in February of 1970, in his first few months as Fed chief, Arthur Burns presided over a stock market that looked eerily like the one of today - failing to make any new highs for more than a few years, then up about six percent in the first two and half months with the new chairman, followed by a sharp twenty percent decline that played out over a period of about six weeks.

Fast forward to today - no new highs in equities for six years, a war with little end in sight, and up until about a week ago under Mr. Bernanke, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had risen about six percent in his first three and a half months. The recent decline of about four percent in rather short order, amid confusing and conflicting statements from the new Federal Reserve Board, has augured in new volatility and may well be a preview of coming attractions.It is on Mr Bernanke' shoulders that investors believe some of the responsibility for the recent bout of market instability lies—though not all of it, by any means. He has yet to establish his credibility with Wall Street: since he took office in February, yields on ten-year bonds, which had been remarkably stable, have climbed by more than half a percentage point. Partly, this has reflected a pick-up in global growth, which tends to push yields up. But recently, it is the component of bond yields that measures inflationary expectations that has increased most sharply.

What was that about risk premiums that the former Fed chair was saying last year? Some reference to history not dealing kindly with "the aftermath of protracted periods of low risk premiums"? Yikes!

...

How much higher inflationary expectations—and to quell them, interest rates—will go is the question. In the months ahead, any hint of a surge will be likely to send markets into spasms, bringing to an end an unusually long placid period that had encouraged investors to embrace the riskiest of asset classes.There are other risks beyond the immediate concern with inflation. If policymakers do respond to rising inflationary expectations by raising interest rates further than they would otherwise have done, the deeply indebted consumers of many English-speaking economies will be hurt. So will the still-giddy housing markets of several countries.

A test of Mr. Bernanke's fire fighting skills has begun - can't wait to see how this turns out.

The skill with which policymakers handle a declining dollar is another cause for concern. The currency has fallen sharply since April 21st, when the G7's finance ministers appeared to endorse a weakening of the dollar by calling on China to let its currency rise. The sense that there may be a concerted effort to weaken the American currency has been nicknamed “Plaza-lite”, after the “Plaza Accord” in 1985 which did just that—with disastrous consequences for stockmarket investors two years later.

Mr Bernanke told Congress last month that because of the size of America's current-account deficit, there was “a small risk of a sudden shift in sentiment that could lead to disruptive changes in the value of the dollar and other asset prices.” He knows that markets are now playing with fire. More bad news on inflation, or any false moves on his part, will heat up inflationary expectations and cause more trouble for the prices of shares, bonds and other assets. What the markets do not yet know—partly because he has not had time to prove himself—is how good Mr Bernanke is with a fire extinguisher.

It was one year later in 1971 that Nixon closed the gold window, severing the last link between gold and paper money, and defaulting on the post World War II Bretton Woods Agreement. There ensued a decade of high commodity prices culminating in Paul Volcker's penal interest rate policies of the 1980s.

Some interesting parallels.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

2 comments:

what would greenspan do?

http://bigpicture.typepad.com/comments/2006/05/wwgd.html

Bookish Ben is in a bit of a pickle.

Post a Comment