Please, Sir, May I Have Another?

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

As we await the results of the bimonthly group therapy session attended by members of the Federal Reserve Board, attention is turned to a recent article($) from The Economist that considers the perils of pausing.

In yet another opinion from yet another anonymous economist at The Economist, the fear of a slowing economy is deemed a lesser threat than an inflation monster left untamed.WHEN Ben Bernanke succeeded Alan Greenspan as the chairman of America's Federal Reserve earlier this year, The Economist's cover illustration depicted Mr Greenspan as a relay runner, passing on a baton, in the form of a lighted stick of dynamite, to his successor. Mr Bernanke, this newspaper suggested, was inheriting an economy in much worse shape than popularly assumed.

Ben Bernanke seems to be getting a lot of unsolicited advice in recent days - none of it likely helps. Six months later, the fuse has burned low, with growth slowing and inflation on the rise. Output grew at an annual rate of just 2.5% in the second quarter of the year, well below capacity. And the speed with which the housing market is cooling suggests that a sharper slowdown may lie ahead. A growing number of commentators are now talking about a recession next year. At the same time, inflation is higher than America's central bankers would like, and increasing. The price gauge that they watch most closely, the deflator for personal consumption expenditure excluding food and energy, went up by an annualised 2.9% between April and June, far above their preferred range of 1-2%. Well over half the components of the consumer-price index are rising at an annual rate above 3%.

Six months later, the fuse has burned low, with growth slowing and inflation on the rise. Output grew at an annual rate of just 2.5% in the second quarter of the year, well below capacity. And the speed with which the housing market is cooling suggests that a sharper slowdown may lie ahead. A growing number of commentators are now talking about a recession next year. At the same time, inflation is higher than America's central bankers would like, and increasing. The price gauge that they watch most closely, the deflator for personal consumption expenditure excluding food and energy, went up by an annualised 2.9% between April and June, far above their preferred range of 1-2%. Well over half the components of the consumer-price index are rising at an annual rate above 3%.

...

Thanks to the weak growth figures, financial markets are betting that the central bankers are more likely to stand pat next week than raise rates again. That would be a mistake. America's economy may be losing steam, but the dangers of rising inflation outweigh those of slowing growth. If Mr Bernanke is prudent, he will increase rates once again.

...

An extended diet of sub-par growth is essential to quell rising price pressure. It is also the only way to unwind the imbalances—households' heavy debts and negative saving rate, the vast current-account deficit—that are the legacy of Mr. Greenspan's loose monetary policy. Few in America like to admit this.

How could it?

The horse has long since left the barn as they say on the ranch - the mare has been gone for about ten years now. The time to have locked the barn door was when the question was first asked, "Is that barn door shut?" That day will have its ten year anniversary in about four months.

From a December 1996 speech that will be remembered for decades to come, we think back:Clearly, sustained low inflation implies less uncertainty about the future, and lower risk premiums imply higher prices of stocks and other earning assets. We can see that in the inverse relationship exhibited by price/earnings ratios and the rate of inflation in the past. But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade? And how do we factor that assessment into monetary policy? We as central bankers need not be concerned if a collapsing financial asset bubble does not threaten to impair the real economy, its production, jobs, and price stability. Indeed, the sharp stock market break of 1987 had few negative consequences for the economy. But we should not underestimate or become complacent about the complexity of the interactions of asset markets and the economy. Thus, evaluating shifts in balance sheets generally, and in asset prices particularly, must be an integral part of the development of monetary policy.

The latest chapter in the history of collapsing financial asset bubbles was written after the stock market crash of 2000.

Is the housing market next?

Think of how different things might have been, if, after the S&P500 had risen nearly 70 percent in the two years prior to this speech, the brakes had been tapped a few times. If, instead of holding rates steady at around five percent, they had been raised a few hundred basis points to quell the animal instincts that were enveloping the nation's equities markets.

Maybe if energy and commodity prices would have risen in the 1990s, things would have been different - the world's economists might not have been so confident of the control that they seemingly exercised at the time.

Maybe if Asian manufacturers had not been so low with their prices, the low-inflation illusion resulting from globalization would not have developed.

Would it have been so bad if, today, businessmen across the land were still complaining that it's impossible to go public - that the technology boom would have come much further had money been made easier?

Would anyone have missed the sock puppets of 2000?

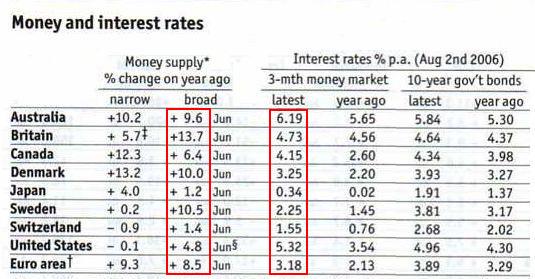

One look at the back of The Economist magazine, and there are more questions to ask. For example, if measured inflation around the world is only a few percent as indicated in these tables... ... then where is all this money going?

... then where is all this money going? And, shouldn't interest rates be much higher than they already are?

And, shouldn't interest rates be much higher than they already are?

What about this table?

Won't these big numbers eventually show up somewhere? How did they get so big in the first place? Did someone make some bad assumptions somewhere along the way?

Mr. Bernanke has an unenviable job to be sure, and another dose of interest rate medicine is probably what the patient needs - it's just a question of whether the patient can handle it.

Having been coddled for almost two decades, the new doctor and the old patient have not yet become accustomed to each others ways - there is no telling what medicine will be delivered or how the patient might react.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

5 comments:

hello from germany,

i´ve read one of the most interresting writings on

http://www.itulip.com/forums/showthread.php?t=292

this posting is about the "conondrum" the despite high rates in 1995 the m3 was explodieng back than and never locked back.

the post is a verly long one but worth reading ist.

very very good!

http://www.immobilienblasen.blogspot.com/

give 'em hell ben .. you can always blame it on greenie

There will be a pause today.

I don't think M3 is the end of it, either; it doesn't count all of the proliferating forms of "credit money". But anyway.

The Economist is wrong. Raising interest rates to put the brakes on inflation won't help. The two kinds of inflation that we are seeing the most are:

(1) housing -- this is "leakage" from the financial economy expansion in broad money (oops!), which is why they've tried to define it out of the CPI.

(2) commodities -- this is structural scarcity due to underinvestment in production and perhaps some instances of true shortage. More or less innocent, though unfortunate.

If the Fed really wants to address the causes of #1, it needs to deflate the financial economy (it could start by actually withdrawing cash and putting the reserve requirement back). Banks don't care what the interest rate is; IMO, they are now making money on money creation itself instead of on the credit spread.

If this is not stopped, it will get worse as the financial economy starts leaking into the real one via a flight to real goods. And all high interest rates will do at that point is (maybe) keep the exchange value of the dollar and the price of gold contained.

[Though an added complexity is that the money that flies overseas instead of to real goods domestically will force the dollar down even more.]

The worst thing an individual investor can do is rely on the Fed to maintain price stability. The Fed's main goal is to placate, and insure, profitability of the big banks and large funds.

How can any rational economist view the monetary history of the last few years as less than complete abdication of responsibility by the Federal Reserve?

Post a Comment