The New GSCI

Wednesday, January 10, 2007

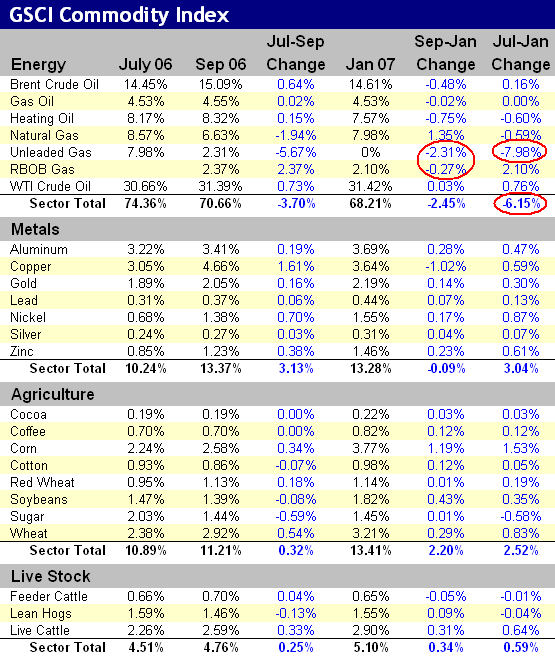

An update on how the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI) has changed over the last six months is shown in the table below.

These changes relate to various theories about how energy prices have been affected during that time, as discussed yesterday and last summer. The net result of all the changes is that gasoline is now weighted at two percent instead of eight percent last July.

The most recent data in the table below appears in the commodities section of the Goldman Sachs website. No historical data could be found - the 2006 data was retrieved after recording it here for other purposes.

There were a number of announcements about changing the gasoline weighting as a result of moving away from the New York Harbor Unleaded Gasoline futures contract to the Reformulated Gasoline Blendstock for Oxygen Blending (RBOB) futures contract - see these notices in June, July, and August. The most recent announcement about the annual re-weighting came earlier in the week.  What this means is that there really is nothing new since last summer's announcement that the weighting of gasoline would be reduced by six percentage points by the end of 2006 as reported in the New York Times - the New York Post story from yesterday seems to be much ado about nothing.

What this means is that there really is nothing new since last summer's announcement that the weighting of gasoline would be reduced by six percentage points by the end of 2006 as reported in the New York Times - the New York Post story from yesterday seems to be much ado about nothing.

The conclusion to this saga does raise the larger question of why the index was changed at all. The explanation from the Goldman Sachs website about how the components are weighted is as follows:Economic Weighting

So, apparently, the production and consumption of gasoline is now surpassed by not only gas oil and gold, but live cattle and corn.

The GSCI is world-production weighted; the quantity of each commodity in the index is determined by the average quantity of production in the last five years of available data. Such weighting provides the GSCI with significant advantages, both as an economic indicator and as a measure of investment performance.

For use as an economic indicator, the appropriate weight to assign each commodity is in proportion to the amount of that commodity flowing through the economy (i.e., the actual production or consumption of that commodity). For instance, the impact that doubling the price of corn has on inflation and on economic growth depends directly on how much corn is used (or produced) in the economy.

From the standpoint of measuring investment performance, production-weighting is not only appropriate but vital. The key to measuring investment performance in a representative fashion is to weight each asset by the amount of capital dedicated to holding that asset. In equity markets, this representative measurement of investment performance is accomplished through weighting indices by market capitalization.

Does that make sense?

There's more gold "flowing through the economy" than gasoline?

For a thorough discussion of the entire mess that Goldman started last summer when the whole thing began, see this fine write-up - many of your questions will be answered there (the author cast the pre-election conspiracy theory in a dismissive light, but liked the Goldman makes even more money conspiracy theory).

As it stands today, the Economic Weighting section of their website appears to be in need of an update.

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

6 comments:

nicely done

That is a very large and arbitrary change, particularly in light of their detailed rationale for how commodities are weighted. In the section on Economic Weighting they should just say, "We're Goldman, we'll do whatever the hell we want."

Thanks for clearing this up... after more reading this is what I suspected as well.

And I also agree... it's still fishy.

Makes good sense to me that Goldman underweights energy and raw materials. It is time for China to do some consuming. The Chinese have very low salaries on a global scale. Right now they can't afford to consume what they make. In order that they can consume tomorrow, that which they can not afford today, their salaries must go up in price and/or the goods they make must drop in price or they need good low interest credit cards. The major inputs to the goods they make are labor and raw materials (and capital). Labor costs must go up not down if the Chinese are to make more money, so raw materials (commodities) will need to drop. Pretty straight forward. Not so fishy.

So, could you also say that high oil price was because of investor demand and not because of actual consumption demand?

BR

Investor demand certainly contributed to higher prices over the last couple years and it will do so again in the future.

Post a Comment